Tibets Complex History India Strategic Crossroads

Tibet’s story is deeply intertwined with India and China, dating back to the 6th Century with the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism. Historically, Tibet functioned as an empire, later falling under Mongol influence and then a unique relationship with the Qing Dynasty. This arrangement, termed sajunu, acknowledged Qing oversight in foreign affairs while granting Tibet internal autonomy a legitimacy constantly questioned due to its reliance on consent, not imposition.

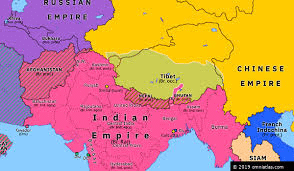

The 19th century saw the Great Game unfold a geopolitical rivalry between the Russian and British Empires for control over Central Asia. Britain, fearing Russian expansion, sought trade access through Tibet. Despite initial agreements, Chinese authority proved ineffective, leading British officials to characterize Chinese suzerainty as a Constitutional Fiction. This culminated in the 1903-1904 military expedition led by Sir Younghusband. While meeting resistance, British forces reached Lhasa and imposed the Convention of Lhasa, demanding a hefty indemnity and control over the Chum Valley a region bordering Sikkim until payment. Essentially, Britain leveraged military force to secure both trade routes and a strategically significant border area.

The 13th Dalai Lama, recognizing the threat, fled Lhasa first to Outer Mongolia, then to Beijing remaining there until 1908 prioritizing his safety and, consequently, the preservation of Tibetan governance. The Qing Dynasty, demonstrating its unreliability, sent Zhao Erfeng to punish Tibet and forcibly integrate it, resulting in the widespread destruction of monasteries in the Kham and Amdo regions. The Dalai Lama was forced to flee again, this time to India in 1910.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 proved pivotal. Zhao Erfengs own soldiers mutinied, beheading him. The Dalai Lama returned from India, expelling Chinese officials. In 1912, Tibet declared its independence, a status it maintained for 36 years, issuing its passports as evidence of sovereignty. However, China embroiled in a civil war, continued to claim Tibet, hampered by internal instability.

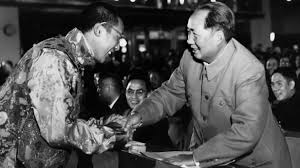

World War II ended, and in 1949, Mao Zedong’s communist forces rose to power in China. Mao, an expansionist leader, immediately instigated repression in Tibet, revitalizing claims of Chinese sovereignty. This sparked resistance in Lhasa but lacked the strength to withstand the impending control. The current Dalai Lama followed in his predecessor’s footsteps, seeking refuge in India in 1959, and establishing a government-in-exile in Dharamshala.

India’s response was heavily influenced by prevailing geopolitical considerations, particularly its budding relationship with the Soviet Union. Following advice from Britain to avoid military intervention or recognizing Tibetan independence due to Tibet’s perceived inability to defend itself, Nehru adopted a policy of strategic ambiguity: offering asylum to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees while maintaining friendly ties with China, aiming to secure India’s borders. This approach, however, ultimately proved unsuccessful China continues to encroach on Indian territory, particularly in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

Looking forward, a shift in India’s policy is essential. Key steps include:

- Publicly acknowledging the Dalai Lama as the leader of the Tibetan people, not just a religious figure.

- Formalizing meetings between Indian politicians/officials and the Dalai Lama.

- Reconsidering the status of the Central Tibetan Administration CTA, upgrading it from NGO status to de facto government.

- Leveraging international pressure alongside allies like the US, who have recently passed the Tibet Act.

- Strengthening border security and recognizing the McMahon Line as the legitimate border with China was established in 1914, but unilaterally disputed by China.

- Proactively addressing the needs of Tibetan refugees in India, streamlining citizenship/OCI Overseas Citizen of India processes.

- Recognizing the ecological significance of Tibet as the source of vital rivers like the Indus and Brahmaputra, and the potential for China to exploit these resources against India’s interests.

India must understand that China is an expansionist power, and a clear, consistent stance on Tibet is crucial. Maintaining the status quo is no longer viable. A multi-pronged approach, combined with international cooperation on issues like Hong Kong, Taiwan, and trade, can create pressure points and potentially compel China to reconsider its position on Tibet. Ultimately, supporting the Tibetan cause is vital for safeguarding their culture, religion, and identity and for securing India’s strategic interests in the region.

Tibet and China: A Historical Knot India Strategic Crossroads

The relationship between Tibet and China is deeply complex, rooted in centuries of shifting power dynamics and punctuated by periods of independence, subjugation, and now, intense Chinese control. Historically, significant Tibetan civilization emerged as early as the 6th century with the introduction of Buddhism. The Tibetan Empire flourished under leaders like Songtsen Gampo, later navigating periods under Mongol rule and the Yuan Dynasty. A key arrangement with the Qing Dynasty established a patron-client relationship: Tibet would acknowledge Chinese authority in external affairs while maintaining autonomy internally. However, this arrangement was built on questionable legitimacy a forced governance lacks true consent.

The 19th century saw the Great Game unfold, with British and Russian empires vying for influence in Central Asia. Tibet became strategically vital: a buffer zone between the expanding Russian and British spheres of influence. Britain sought trade access, but the Qing Dynasty proved unable to enforce its authority in Tibet. This led Britain to view the Qing’s suzerainty as a Constitutional Fiction a facade of control.

In 1903-1904, Britain launched a military expedition led by Sir Younghusband into Tibet, reaching Lhasa and forcing the Convention of Lhasa. The 13th Dalai Lama, fearing for his safety, fled to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing, highlighting Tibet’s vulnerability. Britain secured trade routes and control of the Chumbi Valley a region bordering Sikkim, demanding hefty payments from Tibet. A key quote from the period captures the situation: Sir Francis Younghusband estimated it would take 75 years for Tibet to pay the imposed sum, essentially securing British control for the foreseeable future.

China protested, claiming suzerainty, but Britain pointed out their inability to actually govern Tibet. The Qing Dynasty, belatedly offering to meet the financial demands, proved too late. Soon after, a military commander Zhou Erfeng was sent by the Qing to suppress Tibet and enforce integration, leading to the destruction of monasteries in Kham and Amdo, and forcing the Dalai Lama to flee again this time to India around 1912.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 created a power vacuum. Zhou Erfengs own soldiers mutinied and killed him, leading to the departure of Qing forces. The Dalai Lama returned from India and expelled the Amban the Qing Dynasty resident official, declaring Tibet’s independence in 1912. For the next 36 years, Tibet existed as an independent nation, even issuing its passports as tangible proof of its sovereignty.

However, this independence coincided with internal instability in China a period of warlordism and civil war. When Mao Zedong’s Communist Party won the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the situation drastically changed. Mao, an expansionist leader, viewed Tibet as an integral part of China and initiated a crackdown, triggering widespread repression. This prompted another wave of

where they were welcomed and given refuge, particularly in Dharamshala, which became the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile.

Nehrus India, aligning with a non-aligned foreign policy and focusing on a relationship with the Soviet Union, initially refrained from recognizing Tibetan independence, adhering to the One China policy despite the clear consequences. This proved to be a strategic failure. India’s security was ultimately compromised: China’s continued claims and military expansion resulted in border disputes, like the ongoing contention over Arunachal Pradesh and incursions into Ladakh.

Looking ahead, the video outlines several steps India should take:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: Publicly and consistently identify him not just as a religious leader, but as the leader of the Tibetan people.

- Increase Official Engagement: Facilitate meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders.

- Recognize the Central Tibetan Authority CTA: Upgrade its status from a registered NGO to de facto government recognition.

- Address Refugee Issues: Streamline citizenship processes for Tibetan refugees who have lived in India for generations, perhaps offering OCI Overseas Citizen of India cards.

- Prepare for Succession: Develop a contingency plan for after the Dalai Lamas’s passing, anticipating potential Chinese attempts to install a puppet successor.

- Re-evaluate the One China Policy: Given its limited benefits to India, the time for a review is now.

- Leverage Ecological Concerns: Highlight China’s dam-building activities in Tibet, which threaten water security for India and Southeast Asia.

- International Pressure: Collaborating with allies, like the US, who are increasingly showing support for the Tibetan cause US passed a Tibet Act.

The future of Tibet remains a crucial geopolitical challenge for India. The video argues that a more assertive policy, coupled with strategic alliances and a recognition of Tibet’s unique identity, is essential not only for the Tibetan people but also for India’s security and long-term interests. It acknowledges that change won’t be easy China will react. However, consistent clarity of stance, combined with leveraging multiple pressure points Taiwan, Hong Kong, and trade, will eventually compel China to be more flexible in its approach to Tibet.

British Colonization The Current Tibet Status: A Summary

The story of Tibet is intertwined with the geopolitical ambitions of India and China, stretching back centuries. Initially, Tibet held prominence with strong ties to India from the 6th century, bolstered by Tibetan Buddhism. Though it experienced periods under Mongol and Yuan Dynasty rule, a unique arrangement emerged with the Qing Dynasty. While the Qing claimed legitimacy over Tibet, it largely allowed autonomy in internal affairs – a claim increasingly questioned due to a lack of genuine consent from the Tibetan people.

This delicate balance was disrupted by the Great Game of the 19th century. As Russia expanded southwards and Britain pushed northwards from India, both powers eyed Tibet as a strategic buffer zone. Britain, desiring trade access, sought to influence Tibet, but found the Qing Dynasty unable to enforce its will. British officials realized the purported Chinese suzerainty was largely a constitutional fiction, lacking real control.

This led to the 1903-1904 British military expedition to Tibet, led by Sir Younghusband essentially a temporary invasion. Despite resistance from the Tibetan population, British forces reached Lhasa and signed the Treaty of Lhasa in 1904. Crucially, the 13th Dalai Lama, fearing for his safety, fled to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing, recognizing the precarious situation.

The treaty levied a hefty indemnity on Tibet, with the British threatening to occupy the Chumbi Valley a Tibetan region bordering Sikkim until payment was received. The demand was exorbitant approximately 2.5 million rupees, an amount one British official, Sir Francis Younghusband, estimated would take 75 years to repay. He famously wrote to his wife, noting this would secure British interests and control of the Chumbi Valley for the foreseeable future.

China protested, asserting its suzerainty, but Britain countered that the Chinese authority in Tibet was ineffective. Meanwhile, the Qing Dynasty dispatched Zhao Erfeng, a military commander, to assert control and integrate Tibet, resulting in the destruction of monasteries in Kham and Amdo regions, further fueling unrest. The Dalai Lama was forced to flee again, this time arriving in India for protection in 1908.

The situation dramatically shifted in 1911 with the Fall of the Qing Dynasty. Zhao Erfengs own soldiers mutinied and beheaded him, and Chinese forces withdrew from Tibet. The Dalai Lama returned and expelled the Amban the Qing representative declaring Tibet independent in 1912. This independence lasted for 36 years, signified by the issuance of Tibetan passports recognizing Tibetan sovereignty.

However, China’s claims continued, particularly through internal turmoil and civil war during the early 20th century. After World War II and the 1949 Communist victory led by Mao Zedong, China began enacting a policy of repression and territorial expansion, incorporating Tibet into its control. Tibetan opposition was met with force, and the current Dalai Lama once again sought refuge in India in 1959.

India, influenced by the advice of the British, adopted a cautious approach. It was warned against using military force and advised not to recognize Tibetan independence, fearing it would be unable to defend Tibet against Chinese aggression. This resulted in a policy of maintaining a strategic ambiguity offering shelter to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees but avoiding formal recognition of Tibetan sovereignty and prioritizing relations with China.

This policy, rooted in the hope of friendship with the USSR and China, has proven to be a strategic failure, resulting in ongoing border disputes like in Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh and unresolved security concerns.

Looking ahead, a re-evaluation is needed. Recommendations include:

- Elevating the Dalai Lamas public profile: Identifying him not just as a religious leader, but as the leader of the Tibetan people.

- Official engagement: Facilitating meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders.

- Recognizing the Central Tibetan Authority: Upgrading its status from a non-governmental organization to a de facto government.

- Addressing Tibetan refugee issues: Granting OCI Overseas Citizen of India status to long-term Tibetan refugees.

- Preparing for the future: Developing a strategy for the succession of the Dalai Lama, ensuring it is chosen by the Tibetan people.

- Revisiting McMahon Line: Solidifying recognition of the McMahon Line as the border with China.

- Leveraging international pressure: Coordinating with international powers to pressure China on issues like human rights, environmental concerns Tibetan rivers being crucial water sources, and territorial disputes in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang.

Ultimately, supporting Tibet isn’t just a humanitarian issue; it’s vital for India’s security and regional stability. The Five Fingers analogy used by Mao Zedong with Tibet as the palm and surrounding regions as the finger highlights the strategic importance of this region.

bets Struggle for Independence: A Comprehensive Overview

Tibet’s story is a complex interplay of religious significance, geopolitical strategy, and human rights, deeply entwined with India’s own security. Historically, Tibet served as a buffer between India and China, with noticeable interaction dating back to the 6th century with the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism. The 7th century saw the rise of the Tibetan Empire under leaders like Songtsen Gampo. Later, it came under Mongol and then Yuan Dynasty influence.

A unique, though questionable, arrangement emerged with the Qing Dynasty a suzerainty relationship. This meant the Qing Dynasty managed Tibet’s foreign affairs, but Tibet retained internal autonomy. However, legitimacy hinges on consent, and this was largely absent in this arrangement. As the transcript points out, Legitimacy is based on consent. If you forcibly impose a rule on someone and the people do not follow the laws you set, is it truly valid No.

The situation intensified in the late 19th/early 20th century with the Great Game the imperial rivalry between Russia and Britain for control of Central Asia. Britain, fearing Russian expansion, sought to establish trade routes through Tibet. Their attempts at negotiation with the Qing dynasty were largely unsuccessful, leading to the 1903-1904 British military expedition led by Sir Younghusband.

This expedition, framed as a temporary invasion, met resistance from the Tibetan population. The result was the 1904 Lhasa Convention. Faced with an advancing British force, the 13th Dalai Lama fled to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing for safety a crucial early instance of seeking refuge outside Tibet. As the transcript notes, If the Dalai Lama is safe and secure, the rule is safe and secure.

Britain, ultimately, saw the Qing dynasty’s control over Tibet as largely a Constitutional fiction a claim without genuine authority. They imposed conditions, demanding financial compensation for the expedition and control of the Chumbi Valley a region bordering Sikkim until payment was received. This was partly to clarify the undefined border between Sikkim already under British protection since 1861 and Tibet and also to secure trade access.

China protested, claiming suzerainty, but Britain countered that the Qing Dynasty lacked practical control. The financial demand of 2.5 million rupees was substantial, with Sir Francis Younghusband himself estimating it would take 75 years to pay. He saw this as effectively securing the region for Britain and protecting it from Russian influence in the meantime.

Following the expedition, the Qing sent Zhao Erfeng to punish Tibet and fully integrate it into China. This involved the destruction of monasteries, especially in Kham and Amdo regions, forcing the Dalai Lama to flee again, this time to India around 1959 a pivotal moment that echoes earlier escapes.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 created a power vacuum. Zhao Erfengs own soldiers revolted and beheaded him. The Dalai Lama returned from India, expelled the amban the Qing resident, and in 1912, declared Tibet independent.

For the next 36 years, Tibet remained de facto independent, even issuing its passports documented proof of its sovereignty. However, China, embroiled in civil war and led by figures like Sun Yat-sen, continued to lay claim to Tibet.

The situation radically changed with the rise of Mao Zedong and the Communist Party in 1949. Mao, an expansionist leader, rejected Tibet’s independence and initiated a crackdown. This repression led to further protests in Lhasa and ultimately, a mass exodus of Tibetan refugees to India. India, under Nehru, offered refuge and established settlements for Tibetan refugees, most notably in Dharamshala.

Mao’s strategy involved claiming Tibet the palm and surrounding regions like Ladakh, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Arunachal Pradesh the five fingers. India, advised by Britain, was cautioned against using military force or recognizing Tibetan independence, fearing it would jeopardize its security. This advice rested on the belief that Tibet couldn’t defend itself and aligning with a communist China was crucial, considering the USRs importance. However, this proved to be a strategic failure, evidenced by ongoing border disputes in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

Moving Forward: A Modern Strategy

The transcript clearly outlines a need for policy reassessment. Key steps to consider include:

- Elevating the Dalai Lama Profile: Clearly define his role not just as a religious leader, but as the leader of the Tibetan people in official communications.

- Increased Official Engagement: Facilitate meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian politicians, civil servants, and leaders.

- Recognizing the Central Tibetan Authority CTA: Upgrade the CTA status from an NGO to a de facto government-in-exile.

- Addressing Refugee Needs: Streamline processes for Tibetans-in-exile to obtain OCI Overseas Citizen of India cards, easing mobility and engagement within India.

- Considering Status Similar to Other Persecuted Groups: Offering status similar to that given to minorities fleeing persecution from Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Afghanistan.

- Supporting a Future Dalai Lama Chosen by Tibetans: Ensuring any future Dalai Lama is selected by the Tibetan community, not influenced by China.

India must also leverage broader geopolitical pressure, uniting with countries like the US who have already enacted the Tibet Act and focusing on key pressure points vis–vis China Xinjiang, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and trade. Importantly, India should re-affirm its recognition of the McMahon Line, the border established in the 1914 Shimla Convention, and push back against China’s claims.

Finally, any shift in policy must acknowledge the ecological significance of Tibet as the source of major river systems vital to South and Southeast Asia and the need to protect these resources from Chinese dam construction and potential manipulation.

Ultimately, the future of Tibet remains a crucial geopolitical challenge for India and the international community. A proactive and principled stance, prioritizing the rights and aspirations of the Tibetan people, is essential for regional stability and long-term security. As the transcript powerfully concludes, We have to safeguard their culture, their religion, their identity

India Evolving Response to Tibet: A Strategic Reassessment

India’s relationship with Tibet is a complex one, rooted in centuries of shared history and increasingly defined by strategic considerations in the face of a rising China. Historically, the connection thrived from the 6th century with the spread of Tibetan Buddhism, evolving through periods of Tibetan empire, Mongol influence, and ultimately a unique, though often tenuous, relationship with the Qing Dynasty. This suzerainty where Tibet maintained internal autonomy while acknowledging Qing oversight was always questionable, lacking genuine consent from the Tibetan people.

The 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the Great Game, a geopolitical rivalry between Russia and Britain for control of Central Asia. Britain, seeking to buffer its Indian interests, attempted economic engagement with Tibet. However, the Qing Dynasty’s authority proved weak, leading Britain to view the relationship as largely a Constitutional Fiction. This culminated in the 1903-1904 military expedition led by Sir Younghusband, which pushed into Lhasa and forced the Lhasa Convention. This intervention, while driven by British strategic goals, destabilized the region and prompted the 13th Dalai Lama to flee to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing for safety a precursor to the later flight of the 14th Dalai Lama to India. Specifically, as noted in a letter from Sir Francis Younghusband to his wife at the time, it would take 75 years to recoup the expedition’s costs, effectively securing British influence for decades.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 created a power vacuum. Chinese forces attempted to reassert control, deploying commander Zhao Erfeng to suppress monasteries and integrate Tibet forcefully. This led to another flight of the Dalai Lama – to India in 1912. Following this, Tibet declared independence in 1912 and functioned as a sovereign state for 36 years, even issuing its passports as tangible proof of its independent status.

However, China’s emergence under Mao Zedong in 1949 dramatically altered the landscape. Mao viewed Tibet as an integral part of China and initiated a brutal crackdown, sparking resistance and ultimately the 1959 uprising that forced the current Dalai Lama to seek refuge in India. Nehru’s government, influenced by a desire for a strong relationship with the Soviet Union and a cautiously hopeful view of communist China, adopted a policy of non-interference and refrained from recognizing Tibetan independence. This decision, influenced by British advice not to recognize Tibetan independence due to concerns over Tibet’s military capabilities and potential threats to Indian security, proved strategically questionable. India ended up losing strategic advantages in bordering regions like Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

Nehru and others believed maintaining a friendship with China was paramount, even if it meant compromising on Tibet. However, this strategy proved flawed, as China continued its territorial claims and aggressive posture. Mao’s Five Fingers strategy viewing Ladakh, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Arunachal Pradesh as extensions of Tibet highlighted China’s expansionist ambitions.

Looking Forward: A Revised Approach

Given this historical context and the evolving geopolitical reality, a renewed Indian policy is crucial. A revised strategy should include:

- Elevating the Dalai Lama Profile: Explicitly recognizing the Dalai Lama not simply as a religious leader but as the leader of the Tibetan people.

- Official Engagement: Facilitating high-level meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders.

- De Facto Recognition: Recognizing the Central Tibetan Administration CTA as the de facto government of the Tibetan people – currently registered as an NGO.

- Advocacy for Tibetan Rights: Supporting Tibetan culture, religion and identity.

- Addressing Citizenship Issues: Streamlining the process for Tibetan refugees who qualify for Indian citizenship and offering OCI Overseas Citizen of India cards to those who retain Tibetan identity.

- Preparing for Succession: Developing contingency plans for the Dalai Lamas’s succession, specifically guarding against China potentially installing a puppet successor.

- Revisiting the McMahon Line: Reaffirming India’s recognition of the McMahon Line as the legitimate border demarcation established in 1914, reinforcing border security.

- Leveraging International Pressure: Collaborating with the US and other nations supporting Tibetan rights, potentially utilizing trade and other pressure points to influence China.

India’s policy toward Tibet must move beyond a cautious approach. China’s actions, including dam construction on rivers originating in Tibet, pose long-term ecological and strategic threats to India and the wider region. A proactive stance, supporting the Tibetan cause, protecting Tibetan identity, and bolstering border security aligns with India’s core interests and reinforces its position as a responsible regional power.

Ultimately, recognizing Tibet’s inherent right to self-determination, alongside a robust defense of its own interests, is crucial for India’s long-term security and stability.

Nehrus Policy The Future of Tibet: A Comprehensive Summary

India’s approach to Tibet has been a complex interplay of strategic considerations, historical context, and evolving geopolitical realities. Initially, Tibet served as a buffer state between British India and Tsarist Russia during the Great Game of the 19th and early 20th centuries. British attempts to increase trade were hampered by the Qing Dynasty’s tenuous control a Constitutional Fiction as the transcript puts it where outward legitimacy consent of the governed was questionable. The 1903-1904 British expedition led by Sir Younghusband, while ostensibly about trade, was a military incursion intended to prevent Russian expansion. The resulting 1904 Convention, signed with the 13th Dalai Lama who soon fled to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing for safety imposed financial burdens on Tibet and attempted to clarify the border with Sikkim a border previously unclear since Sikkim came under British protection in 1861.

China, claiming suzerainty, protested this direct treaty with Tibet, asserting its right to negotiate. However, Britain pointed out the weakness of China’s claim, as its representatives lacked authority. The Qing Dynasty eventually offered to cover the expedition costs a significant 2.5 million rupees a sum estimated to take 75 years to repay, as noted in a letter from Sir Francis Younghusband to his wife. This underscored the artificiality of China’s claim at that time.

Following the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, Tibetan forces expelled Chinese administrators, and in 1912, Tibet declared its independence, lasting for 36 years. During this period, Tibet issued its passports, demonstrating its de facto sovereignty a copy of which is documented in the transcript. This period of independence coincided with internal turmoil in China, marked by civil war between Nationalist and Communist forces.

The situation drastically shifted in 1949 with the rise of Mao Zedong and the Communist victory. Mao viewed Tibet as an integral part of China and initiated repression, leading to increased unrest and, crucially, the Dalai Lamas flight to India in 1959. India, under Nehru, granted him asylum and established a Tibetan government-in-exile in Dharamsala.

However, Nehru’s policy, influenced by a desire for a strong relationship with the USSR perceived as strategically important and a reluctance to antagonize China, was to avoid recognizing Tibetan independence and refrain from using military force. British advisors echoed this caution, fearing Tibet’s inability to defend itself. This was a critical strategic failure, leading to continued Chinese encroachment and unresolved border disputes in regions like Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. The five fingers metaphor used by Mao Tibet as the palm and surrounding regions as fingers highlights China’s expansionist intent.

The Core Problem Proposed Solutions:

The transcript identifies several key steps India should consider moving forward:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: Consistently identify him as the Leader of the Tibetan People, not just a religious figure, in official communications and engagements.

- Official Meetings: Facilitate meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders to signal recognition of Tibetan concerns.

- Nobel Recognition Government Status: Acknowledge the Central Tibetan Authority CTA beyond its current NGO status granting it de facto government recognition. This would facilitate access to Indian state functions and provide administrative support.

- OCI Status for Tibetans: Provide Overseas Citizen of India OCI cards to Tibetan refugees who qualify, easing mobility and engagement.

- Prepare for Succession: Develop a contingency plan for the Dalai Lamas’s passing, anticipating potential Chinese attempts to install a puppet successor. India must have a clear counter-strategy.

- Clarify Boundary Disputes: Reiterate the recognition of the McMahon Line, established in the 1914 Shimla Convention signed by British India and Tibet but not China, as the legitimate border with Arunachal Pradesh.

- Leverage Multilateral Pressure: Work with other nations like the US, which has its own Tibet policy and passed the Support Act to collectively pressure China. This includes raising concerns about ecological issues Tibetan rivers are crucial water sources for the region and broader human rights abuses.

The Core Argument: The transcript advocates for a bolder Indian policy towards Tibet, recognizing that a passive approach has yielded limited benefits. It emphasizes the importance of safeguarding Tibetan culture, religion, and identity, and moving beyond the constraints of the One China policy which hasn’t demonstrably secured India’s interests.

Ultimately, the future of Tibet remains a crucial geopolitical challenge. The transcript argues that supporting Tibet isnt merely a matter of humanitarian concern, but a strategic imperative for India’s security and the broader stability of the region. It posits that a proactive approach is not about inciting conflict, but about asserting India’s interests and preparing for a future where China’s influence may wane

Maos Expansionism and the Fate of Tibet: A Strategic Overview

Maos China fundamentally altered the landscape of Tibet, transforming a historically autonomous region into a point of contention with India. This wasn’t a sudden event, but the culmination of decades of shifting power dynamics starting in the 19th century. Initially, Tibet navigated a precarious space between a weakening Qing Dynasty China and an expanding British India during the Great Game a geopolitical rivalry for control of Central Asia. British interests focused on trade and preventing Russian influence, leading to the 1903-1904 military expedition led by Sir Younghusband. This expedition, while presented as a trade mission, was essentially a temporary invasion, ultimately forcing the 13th Dalai Lama into exile to Outer Mongolia, and later Beijing, for safety.

The British recognized the existing Sajanu system as a nominal Chinese suzerainty over Tibet allowing for internal autonomy as largely a Constitutional Fiction, a facade lacking genuine legitimacy due to a lack of consent from the Tibetan population. As one historical account notes, the financial demands imposed on Tibet by the British were so exorbitant it would take 75 years to pay Sir Francis Younghusband himself acknowledged in a letter to his wife that while securing the Chum Valley a border region with Sikkim was his primary goal, it would be maintained until 75 years from now effectively acknowledging a long-term occupation rather than genuine accord.

China, attempting to assert its authority, offered to pay the demanded sum, highlighting that Tibet lacked the funds. This triggered a period of Chinese military intervention under commander Zhao Erfeng around 1908, aiming for full integration. Zhao Erfeng systematically destroyed monasteries in the Kham and Amdo regions a brutal attempt at cultural suppression forcing the Dalai Lama into another exile, this time to India in 1959, seeking refuge.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 created a power vacuum, and the Dalai Lama returned to Tibet, expelling Chinese officials. For the next 36 years, Tibet operated as a de facto independent state, issuing its passports tangible evidence of its sovereignty. However, this period of independence coincided with internal turmoil in China, including a civil war between Nationalists and Communists.

When Mao Zedong came to power in 1949, his expansionist ambitions directly threatened Tibet. Mao viewed Tibet as an integral part of China and launched a campaign of repression. This prompted large numbers of Tibetan refugees to seek asylum in India, which provided them with shelter and established refugee camps, notably in Dharamshala, where the current Dalai Lama established a government-in-exile.

Mao envisioned Tibet as the palm with surrounding regions Ladakh, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Arunachal Pradesh as its five fingers, all destined to be part of China. India, seeking to navigate this complex situation, received advice from the British urging against military intervention or formal recognition of Tibetan independence, fearing Tibet could not defend itself. Nehru, then Prime Minister of India, prioritized relations with the USSR, seeing Communist China as a potential ally, leading to a policy of cautious engagement. This proved to be a strategic failure the lack of a strong response emboldened China’s continued aggression, leading to ongoing border disputes in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

Current and Future Strategies

Given China’s unwavering expansionist tendencies, reassessing India’s policy towards Tibet is crucial. Several steps can be taken:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: Officially recognizing him not merely as a religious leader, but as the leader of the Tibetan people in all official communication.

- Facilitate Increased Engagement: Regular, high-level meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders and civil servants, signaling clear support for Tibetan autonomy.

- Recognize the Tibetan Government-in-Exile CTA: Upgrading the CTA status from an NGO to a de facto government, providing it access to Indian state functions and resources. Acknowledging this status is vital despite anticipating Chinese protests. As the transcript notes, History has shown that European colonial powers…became insignificant economically and politically. China may be economically and militarily powerful now, but that won’t always be the case.

- Revise the One China Policy: Given the ongoing threats to India’s territorial integrity in Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, and the lack of concessions from China, a reassessment is vital.

- Address Refugee Needs: Streamlining citizenship procedures for Tibetan refugees who qualify but have taken citizenship elsewhere, providing them with OCI Overseas Citizen of India cards for easier travel and engagement.

- Prepare for Succession: The Dalai Lamas’s health is fragile. India must prepare for his passing and actively work to prevent China from installing a puppet successor.

- Highlight Ecological Concerns: Tibet is the source of many major Asian rivers. Chinese dam construction poses a significant threat to water security in India and Southeast Asia. Raising this issue internationally is critical.

- Leverage Geopolitical Alliances: Collaborate with nations like the US which has already passed supportive legislation like the Tibetan Policy Act to pressure China on Tibet.

China will undoubtedly react to any shift in India’s policy. However, as the transcript emphasizes, When you make a change in your stance and you continue with it, others are going to adjust accordingly. A firm, consistent stance combined with a robust response to ecological threats and strategic engagement with international allies could create the necessary leverage to pursue a more favorable outcome for Tibet and ensure India’s long-term security in the region.

The Struggle for Tibet: A Summary of the Situation India Path Forward

The situation in Tibet is a complex geopolitical challenge deeply intertwined with India’s security and future. Historically, Tibet served as a buffer state between India and China, with significant cultural and religious ties to India dating back to the 6th century with the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Qing Dynasty exerted some influence suzerainty, it largely allowed Tibet internal autonomy a legitimacy questioned due to its lack of genuine consent from the Tibetan people.

The 19th century saw British involvement fueled by the Great Game a strategic rivalry with Russia for dominance in Central Asia. Worried about Russian expansion, the British sought trade access through Tibet. The 1903-1904 military expedition led by Sir Younghusband, though presented as a diplomatic mission, was effectively a temporary invasion. The subsequent 1904 Lhasa Convention, signed with Tibetan leaders, aimed to secure trade routes and establish a clear border with Sikkim which was already under British protection. This treaty, however, was deemed a Constitutional Fiction by the British themselves, as the Chinese suzerainty lacked real authority. The expedition forced the 13th Dalai Lama into exile, first to Outer Mongolia and then to Beijing, to ensure his safety.

China, recognizing its weakening control, offered to pay the expedition costs a sum estimated to take 75 years to repay, as noted in a letter from Sir Francis Younghusband to his wife. This highlights the true motivations behind China’s claim of suzerainty. Following a crackdown by China Zhao Erfeng, tasked with integrating Tibet, the Dalai Lama again fled this time to India in 1959, seeking refuge from escalating Chinese repression.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 offered a period of independence for Tibet, lasting until 1949 when Mao Zedongs communist forces seized power in China. Mao immediately viewed Tibet as an integral part of China, initiating a renewed and brutal crackdown on Tibetan culture and religion. The Indian response, heavily influenced by then-Prime Minister Nehru’s commitment to fostering relations with the USSR China’s Communist ally, resulted in a hesitant approach. India, advised by Britain, adopted a policy of non-recognition of Tibetan independence and avoided military intervention, prioritizing its security. Nehru believed a strong relationship with China was paramount, a strategy that proved strategically flawed, failing to protect its borders Ladhak and Arunachal Pradesh or advancing India’s interests.

Currently, over 100,000 Tibetan refugees reside in India, many established in camps like those in Delhi and around Dharamsala where the Dalai Lama established a government-in-exile. China’s expansionist ambitions, repeatedly articulated with the Five Fingers metaphor Ladhak, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Arunachal Pradesh representing the fingers while Tibet is the palm, remain a clear threat.

What should India do now?

A shift in policy is crucial. India must:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: Consistently refer to him as the Leader of the Tibetan People rather than solely a religious figure, emphasizing his political role.

- Formalize Engagement: Increase official meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian leaders.

- Recognize the Central Tibetan Authority: Upgrade its status from a registered NGO to de facto government recognition, providing access to Indian institutions and facilitating engagement.

- Prioritize Citizenship Support: Streamline the process for Tibetan refugees who qualify for Indian citizenship and offer OCI cards to those who obtained foreign citizenship to ensure easy mobility.

- Address Ecological Concerns: Recognize that Tibet is the source of many major Asian rivers and China’s dam-building practices pose a serious threat to regional water security.

- Re-evaluate the One China Policy: Given its lack of tangible benefits, it is time to reassess this policy, especially considering China’s continued aggressive stance.

- Leverage International Pressure: Collaborate with nations like the US which has passed the Tibetan Policy Act and others to pressure China on human rights and Tibetan autonomy.

- Plan for the Future: Prepare a succession plan for the Dalai Lama, crucial to prevent China from installing a puppet leader.

India’s actions should be guided by a long-term understanding that supporting the Tibetan cause isn’t just a moral imperative, but a strategic necessity. India must proactively safeguard Tibetan culture, religion, and identity. A collective approach, leveraging pressure points like Xinjiang, Taiwan, and trade, will be key to influencing China and safeguarding the future of Tibet as a crucial geopolitical region.

The Dalai Lamas’s Role and India’s Strategic Calculus on Tibet

The situation in Tibet is a complex interplay of history, geopolitics, and religious identity. Historically, Tibet enjoyed periods of independence and autonomy, notably under the 7th-century Tubo Empire and later through a relationship with the Qing Dynasty a relationship characterized by Tibetan internal rule despite Qing oversight of foreign affairs. This arrangement, however, lacked genuine consent from the Tibetan population, rendering its legitimacy questionable.

The Great Game of the 19th century a rivalry between the British and Russian Empires for dominance in Central Asia brought increased scrutiny to Tibet. Britain, fearing Russian expansion, sought trade through Tibet. When the Qing Dynasty proved unable to enforce British trade interests, Britain launched a military expedition in 1903-1904, led by Sir Younghusband, reaching Lhasa and forcing the Tibetans to sign the Treaty of Lhasa. This treaty outlined monetary demands and control over the Chumbi Valley a strategic border region with Sikkim effectively leveraging territorial control for financial gain. The 13th Dalai Lama, recognizing the threat, fled to Outer Mongolia and later Beijing for safety. A letter from Sir Francis Younghusband even acknowledged the long-term implications, suggesting securing the region would take 75 years

China asserted sovereignty, offering to pay the demanded sum, but the British viewed the Qing claim as a constitutional fiction existing more in theory than in practice. Following the expedition, the Qing Dynasty sent General Zhao Erfeng to consolidate control, resulting in the destruction of monasteries in Kham and Amdo regions, forcing the Dalai Lama to once again flee, this time to India in 1910.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 presented an opportunity. Zhao Erfengs own soldiers mutinied and killed him, and the Dalai Lama returned to Tibet, expelling the Qing representatives. By 1912, Tibet officially declared its independence, remaining so for 36 years, issuing its passports as proof of self-governance. This period ended with the rise of Mao Zedong in 1949, who began a campaign to reassert Chinese control, triggering repression and a mass exodus of Tibetans to India.

India, under Nehru, adopted a cautious approach, influenced by a desire to maintain friendly relations with the Soviet Union and a belief that Tibet couldn’t independently defend itself. British advisors cautioned against military intervention or recognizing Tibet’s independence. This led to the One China policy and ultimately, a strategic failure India’s security concerns regarding Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh remain unmet even today.

Looking forward, a shift in India’s strategy is warranted. Key steps include:

- Elevating the Dalai Lama Profile: Consistently framing him as the Leader of the Tibetan People, not just a religious figure, in official communications.

- Increased Official Engagement: Establishing regular meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders, signaling recognition.

- Recognizing the Central Tibetan Authority: Upgrading its status from an NGO to a de facto government. This would unlock access to Indian state functions and provide a formal channel for dialogue.

- Addressing Refugee Needs: Facilitating OCI Overseas Citizen of India cards for Tibetan refugees who qualify.

- Preparing for Succession: Acknowledging the potential difficulties surrounding a future Dalai Lama, with a strategy to counter any attempt by China to install a puppet.

- Revisiting the McMahon Line: Firmly recognizing the 1914 McMahon Line as the border with China as established in the Shimla Convention which China did not sign, but Tibet and British India did.

- Leveraging International Pressure: Coordinating with nations like the US who, through the recent Tibet Act, are demonstrating support for the Tibetan cause.

Beyond these political and diplomatic actions, India must acknowledge the ecological stakes. Tibet is the source of numerous major Asian rivers; Chinese control over the region presents risks to water security across the continent.

Ultimately, a proactive and clear stance on Tibet not only supports the Tibetan people’s quest for self-determination but also safeguards India’s long-term strategic interests and regional stability. As the transcript notes, a clear stance even if initially met with resistance ultimately prompts others to adjust.

Maos Expansionism and the Fate of Tibet: A Strategic Overview

Maos China fundamentally altered the landscape of Tibet, transforming a historically autonomous region into a point of contention with India. This wasn’t a sudden event, but the culmination of decades of shifting power dynamics starting in the 19th century. Initially, Tibet navigated a precarious space between a weakening Qing Dynasty China and an expanding British India during the Great Game a geopolitical rivalry for control of Central Asia. British interests focused on trade and preventing Russian influence, leading to the 1903-1904 military expedition led by Sir Younghusband. This expedition, while presented as a trade mission, was essentially a temporary invasion, ultimately forcing the 13th Dalai Lama into exile to Outer Mongolia, and later Beijing, for safety.

The British recognized the existing Sajanu system as a nominal Chinese suzerainty over Tibet allowing for internal autonomy as largely a Constitutional Fiction, a facade lacking genuine legitimacy due to a lack of consent from the Tibetan population. As one historical account notes, the financial demands imposed on Tibet by the British were so exorbitant it would take 75 years to pay Sir Francis Younghusband himself acknowledged in a letter to his wife that while securing the Chum Valley a border region with Sikkim was his primary goal, it would be maintained until 75 years from now effectively acknowledging a long-term occupation rather than genuine accord.

China, attempting to assert its authority, offered to pay the demanded sum, highlighting that Tibet lacked the funds. This triggered a period of Chinese military intervention under commander Zhao Erfeng around 1908, aiming for full integration. Zhao Erfeng systematically destroyed monasteries in the Kham and Amdo regions a brutal attempt at cultural suppression forcing the Dalai Lama into another exile, this time to India in 1959, seeking refuge.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 created a power vacuum, and the Dalai Lama returned to Tibet, expelling Chinese officials. For the next 36 years, Tibet operated as a de facto independent state, issuing its passports tangible evidence of its sovereignty. However, this period of independence coincided with internal turmoil in China, including a civil war between Nationalists and Communists.

When Mao Zedong came to power in 1949, his expansionist ambitions directly threatened Tibet. Mao viewed Tibet as an integral part of China and launched a campaign of repression. This prompted large numbers of Tibetan refugees to seek asylum in India, which provided them with shelter and established refugee camps, notably in Dharamshala, where the current Dalai Lama established a government-in-exile.

Mao envisioned Tibet as the palm with surrounding regions Ladakh, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Arunachal Pradesh as its five fingers, all destined to be part of China. India, seeking to navigate this complex situation, received advice from the British urging against military intervention or formal recognition of Tibetan independence, fearing Tibet could not defend itself. Nehru, then Prime Minister of India, prioritized relations with the USSR, seeing Communist China as a potential ally, leading to a policy of cautious engagement. This proved to be a strategic failure the lack of a strong response emboldened China’s continued aggression, leading to ongoing border disputes in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

Current and Future Strategies

Given China’s unwavering expansionist tendencies, reassessing India’s policy towards Tibet is crucial. Several steps can be taken:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: Officially recognizing him not merely as a religious leader, but as the leader of the Tibetan people in all official communication.

- Facilitate Increased Engagement: Regular, high-level meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders and civil servants, signaling clear support for Tibetan autonomy.

- Recognize the Tibetan Government-in-Exile CTA: Upgrading the CTA status from an NGO to a de facto government, providing it access to Indian state functions and resources. Acknowledging this status is vital despite anticipating Chinese protests. As the transcript notes, History has shown that European colonial powers…became insignificant economically and politically. China may be economically and militarily powerful now, but that won’t always be the case.

- Revise the One China Policy: Given the ongoing threats to India’s territorial integrity in Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, and the lack of concessions from China, a reassessment is vital.

- Address Refugee Needs: Streamlining citizenship procedures for Tibetan refugees who qualify but have taken citizenship elsewhere, providing them with OCI Overseas Citizen of India cards for easier travel and engagement.

- Prepare for Succession: The Dalai Lamas’s health is fragile. India must prepare for his passing and actively work to prevent China from installing a puppet successor.

- Highlight Ecological Concerns: Tibet is the source of many major Asian rivers. Chinese dam construction poses a significant threat to water security in India and Southeast Asia. Raising this issue internationally is critical.

- Leverage Geopolitical Alliances: Collaborate with nations like the US which has already passed supportive legislation like the Tibetan Policy Act to pressure China on Tibet.

China will undoubtedly react to any shift in India’s policy. However, as the transcript emphasizes, When you make a change in your stance and you continue with it, others are going to adjust accordingly. A firm, consistent stance combined with a robust response to ecological threats and strategic engagement with international allies could create the necessary leverage to pursue a more favorable outcome for Tibet and ensure India’s long-term security in the region.

The Struggle for Tibet: A Summary of the Situation India Path Forward

The situation in Tibet is a complex geopolitical challenge deeply intertwined with India’s security and future. Historically, Tibet served as a buffer state between India and China, with significant cultural and religious ties to India dating back to the 6th century with the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism. While the Qing Dynasty exerted some influence suzerainty, it largely allowed Tibet internal autonomy a legitimacy questioned due to its lack of genuine consent from the Tibetan people.

The 19th century saw British involvement fueled by the Great Game a strategic rivalry with Russia for dominance in Central Asia. Worried about Russian expansion, the British sought trade access through Tibet. The 1903-1904 military expedition led by Sir Younghusband, though presented as a diplomatic mission, was effectively a temporary invasion. The subsequent 1904 Lhasa Convention, signed with Tibetan leaders, aimed to secure trade routes and establish a clear border with Sikkim which was already under British protection. This treaty, however, was deemed a Constitutional Fiction by the British themselves, as the Chinese suzerainty lacked real authority. The expedition forced the 13th Dalai Lama into exile, first to Outer Mongolia and then to Beijing, to ensure his safety.

China, recognizing its weakening control, offered to pay the expedition costs a sum estimated to take 75 years to repay, as noted in a letter from Sir Francis Younghusband to his wife. This highlights the true motivations behind China’s claim of suzerainty. Following a crackdown by China Zhao Erfeng, tasked with integrating Tibet, the Dalai Lama again fled this time to India in 1959, seeking refuge from escalating Chinese repression.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 offered a period of independence for Tibet, lasting until 1949 when Mao Zedongs communist forces seized power in China. Mao immediately viewed Tibet as an integral part of China, initiating a renewed and brutal crackdown on Tibetan culture and religion. The Indian response, heavily influenced by then-Prime Minister Nehru’s commitment to fostering relations with the USSR China’s Communist ally, resulted in a hesitant approach. India, advised by Britain, adopted a policy of non-recognition of Tibetan independence and avoided military intervention, prioritizing its security. Nehru believed a strong relationship with China was paramount, a strategy that proved strategically flawed, failing to protect its borders Ladhak and Arunachal Pradesh or advancing India’s interests.

Currently, over 100,000 Tibetan refugees reside in India, many established in camps like those in Delhi and around Dharamsala where the Dalai Lama established a government-in-exile. China’s expansionist ambitions, repeatedly articulated with the Five Fingers metaphor Ladhak, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, and Arunachal Pradesh representing the fingers while Tibet is the palm, remain a clear threat.

What should India do now?

A shift in policy is crucial. India must:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: Consistently refer to him as the Leader of the Tibetan People rather than solely a religious figure, emphasizing his political role.

- Formalize Engagement: Increase official meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian leaders.

- Recognize the Central Tibetan Authority: Upgrade its status from a registered NGO to de facto government recognition, providing access to Indian institutions and facilitating engagement.

- Prioritize Citizenship Support: Streamline the process for Tibetan refugees who qualify for Indian citizenship and offer OCI cards to those who obtained foreign citizenship to ensure easy mobility.

- Address Ecological Concerns: Recognize that Tibet is the source of many major Asian rivers and China’s dam-building practices pose a serious threat to regional water security.

- Re-evaluate the One China Policy: Given its lack of tangible benefits, its time to reassess this policy, especially considering Chinas continued aggressive stance.

- Leverage International Pressure: Collaborate with nations like the US which has passed the Tibetan Policy Act and others to pressure China on human rights and Tibetan autonomy.

- Plan for the Future: Prepare a succession plan for the Dalai Lama, crucial to prevent China from installing a puppet leader.

India’s actions should be guided by a long-term understanding that supporting the Tibetan cause isn’t just a moral imperative, but a strategic necessity. India must proactively safeguard Tibetan culture, religion, and identity. A collective approach, leveraging pressure points like Xinjiang, Taiwan, and trade, will be key to influencing China and safeguarding the future of Tibet as a crucial geopolitical region.

Indias Tibet Policy: A Critical Crossroads

India’s current approach to Tibet is a complex balancing act, rooted in historical ties, strategic concerns, and evolving geopolitical realities. Historically, India and Tibet enjoyed a strong relationship, with Tibetan Buddhism deeply influencing Indian culture beginning in the 6th century. The Tibetan Empire flourished, experiencing periods of autonomy even while acknowledging nominal Chinese suzerainty under dynasties like the Qing. However, this suzerainty was always questionable legitimacy requires consent, and Tibetans largely resisted complete control.

The 19th-century Great Game the rivalry between Britain and Russia for dominance in Central Asia brought Tibet into focus. Britain, fearing Russian expansion, sought trade access through Tibet, but found the Qing dynasty unable to enforce its claims. This led to the 1903-1904 British expedition led by Sir Younghusband, a military intervention justified as securing trade routes. The resulting 1904 Lhasa Convention, signed with the 13th Dalai Lama who was forced to flee to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing for safety, exposed the fictional nature of Chinese control. Britain imposed financial demands and threatened occupation of the Chumbi Valley a region bordering Sikkim to secure concessions. A letter from Sir Francis Younghusband predicted it would take 75 years for Tibet to pay the imposed sum underscoring the exploitative nature of the arrangement.

Ultimately, the Qing dynasty funded the indemnity, claiming sovereignty. This prompted a crackdown on Tibet by the Qing, sending commander Zhao Erfeng to suppress dissent and integrate Tibet fully. This reignited unrest, and the Dalai Lama was again forced to flee, eventually arriving in India in 1910. This initial arrival predates the more well-known flight of the current Dalai Lama in 1959.

The fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 provided an opportunity. Zhao Erfengs own soldiers mutinied and killed him. The Dalai Lama returned from India, expelled Chinese officials, and in 1912, declared Tibet independent. Tibet remained independent for 36 years, issuing its passports a clear indication of sovereignty. However, China was undergoing internal turmoil, including a civil war and ultimately the rise of the Communist Party under Mao Zedong in 1949. Mao, pursuing an expansionist agenda, once again asserted Chinese control over Tibet, leading to repression and another wave of Tibetan refugees seeking asylum in India.

India, under Nehru, adopted a cautious policy offering asylum to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees while attempting to maintain friendly relations with China a strategy arguably born of the perceived need for Soviet support. This policy, however, proved strategically flawed. Despite prioritizing relations with Beijing, India faced border disputes in Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, demonstrating China’s disregard for Indian concerns. Nehru believed maintaining ties with the USSR and China was paramount, but this did not translate into security.

The current situation demands a policy reassessment. A complete abandonment of the status quo is necessary while acknowledging the Tibetan aspiration for self-determination isn’t going anywhere. Key steps India should take include:

- Elevating the Dalai Lama profile: Consistently referring to him as the leader of the Tibetan people, not merely a spiritual leader, in official communications.

- Increased official engagement: Facilitating meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian political leaders to signal support for Tibetan legitimacy.

- Recognizing the Central Tibetan Administration CTA: Upgrading the CTA status from a non-governmental organization to a de facto government-in-exile. This would grant them greater access to Indian institutions and international forums.

- Supporting Tibetan identity preservation: Offering Overseas Citizen of India OCI cards to Tibetan refugees who lost their citizenship upon leaving Tibet, streamlining their access and integration.

- Addressing future leadership: Developing a contingency plan for the succession of the Dalai Lama, preemptively countering any attempt by China to install a puppet successor.

- Ecological concerns: Tibet is the source of many major rivers which flow into South East Asia. China’s control over the region could result in downstream hardship.

- Leveraging geopolitical pressure: India should actively collaborate with countries critical of China like the US to increase pressure on human rights issues in Tibet and strengthen support for Tibetan autonomy, and using pressure points like trade, the status of Hong Kong, and human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Indias historical policy, influenced by a desire for regional stability and a focus on its relationship with China, has arguably failed to secure its own interests. When you make a change in your stand and you continue with it, gradually others are going to adjust according to you. Ignoring the Tibetan cause is no longer a viable option. The future requires a proactive approach that protects Tibetan culture, supports the Tibetan people, and safeguards Indias own strategic and ecological security. The challenge remains crucial in India’s neighborhood.

The Geopolitical Tightrope: Tibet, India, and a Shifting Future

The current status of Tibet is a complex geopolitical issue deeply intertwined with India’s security and strategic interests. Historically, Tibet served as a buffer state between India and China, with significant cultural and religious ties to India dating back to the 6th century with the spread of Tibetan Buddhism. While nominally under Chinese suzerainty beginning with the Yuan Dynasty, Tibet maintained significant autonomy a situation rooted in a questionable legitimacy due to lack of genuine consent from the Tibetan population.

This delicate balance was severely disrupted by British involvement in the early 20th century. Driven by The Great Game a geopolitical rivalry with Russia for dominance in Central Asia Britain sought trade routes through Tibet. Despite assurances from the Qing Dynasty, British influence was limited, leading to a military expedition 1903-1904 led by Sir Younghusband. This expedition, while ostensibly about trade, effectively functioned as a temporary invasion, forcing a treaty the Lhasa Convention upon Tibet. The 13th Dalai Lama, recognizing the precarious situation, fled to Outer Mongolia and then Beijing for safety, illustrating the tenuous nature of Chinese control. As British diplomat Sir Francis Younghusband himself wrote in a letter, resolving the financial demands imposed on Tibet would take 75 years a tacit acknowledgment of the instability.

China asserted its suzerainty by providing the demanded funds, but this claim was undermined by the fact that the Qing Dynasty lacked the power to enforce its will within Tibet. A subsequent punitive military campaign by a Chinese commander, Zhao Erfeng, only further alienated the Tibetan population and forced the Dalai Lama into another exile.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 provided a crucial opportunity. The Dalai Lama returned to Tibet and expelled Chinese representatives, declaring Tibet independent in 1912, a status that lasted for 36 years. During this period, Tibet even issued its own passports a clear indication of sovereignty. However, this independence coincided with internal turmoil in China, including a civil war, and a lack of consistent international recognition.

The situation drastically changed following the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949 under Mao Zedong. Mao viewed Tibet as integral to China, initiating a brutal crackdown and repression of Tibetan culture. This prompted another wave of Tibetan refugees, including the current Dalai Lama, to seek asylum in India. India, under Nehru, adopted a policy of welcoming refugees and establishing settlements like those in Dharamshala, allowing a Tibetan government-in-exile to function. This decision, while humanitarian, was coupled with a strategic calculation: maintaining friendly relations with the Soviet Union meant prioritizing relations with Communist China.

However, this strategy proved to be a failure. China continued its expansionist policies, challenging India’s territorial claims in both Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. India’s attempts to remain neutral and appease China have yielded little.

The Path Forward: A Multi-Pronged Approach

Recognizing the limitations of past approaches, a shift in India’s Tibet policy is now crucial. This requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Elevate the Dalai Lama Profile: India must consistently refer to the Dalai Lama as the leader of the Tibetan people, not just as a religious figure, in all official communications and interactions.

- Formalize Engagement: Initiate regular official meetings between the Dalai Lama and Indian politicians, civil servants, and leaders.

- Recognize the Central Tibetan Authority CTA: Upgrade the CTA status from a registered NGO to a de facto government.

- Address Refugee Needs: Streamline the process for Tibetan refugees qualifying for Indian citizenship or offer Overseas Citizen of India OCI cards to those who have taken citizenship elsewhere but wish to maintain ties.

- Revisit the McMahon Line: Reaffirm India’s recognition of the McMahon Line established in 1914 as the legitimate border with China in Arunachal Pradesh. Support for Tibet does not negate India’s existing border disputes but enhances its leverage.

- Prepare for Succession: The Dalai Lamas’s health is declining, making it essential to develop a counter-strategy to prevent China from installing a puppet successor.

- Leverage International Pressure: Actively collaborate with nations like the US which has passed the Tibetan Policy Act to increase international pressure on China.

Beyond Geopolitics: The Ecological Dimension

The importance of Tibetan autonomy isnt limited to geopolitics. Tibet is the source of several major Asian rivers, including the Indus and Brahmaputra. China’s dam-building activities pose significant ecological risks, potentially impacting water security across the region. Protecting Tibet’s environment is therefore vital for the long-term stability of South and Southeast Asia.

India must understand that a passive approach to Tibet is no longer tenable. China’s rise is not indefinitely sustainable. By steadfastly supporting the Tibetan cause and protecting its culture, religion, and identity India can ultimately strengthen its security and contribute to a more balanced and stable regional order. A strong and autonomous Tibet is not just a moral imperative but a strategic necessity.

Economic and Ecological Concerns Related to Tibet

The status of Tibet has been a contentious issue for centuries, with various empires and dynasties vying for control over the region. In the 7th century, Tibet was a powerful empire under the leadership of Songtsen Gampo, and later it was under the Mongol Empire. However, in the 13th century, the Yuan Dynasty took control of Tibet, followed by the Ming Dynasty.

The British Expedition and the Lhasa Convention

In 1903, the British launched a military expedition to Tibet, led by Sir Francis Younghusband, to expand British trade and influence in the region. The expedition was successful, and the Lhasa Convention was signed in 1904, which recognized British control over Tibet.

Chinese Claim over Tibet

However, the Chinese government claimed sovereignty over Tibet, and in 1911, the Chinese Revolution led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty. The Chinese government then sent a military commander, Zhao Erfeng, to Tibet to assert Chinese control. The Dalai Lama, who was the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet, fled to India for safety.

Tibets Independence and China Claim

In 1912, the Dalai Lama declared Tibet’s independence, and the Tibetan government was established. However, the Chinese government continued to claim sovereignty over Tibet. In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party came to power, and Mao Zedong declared that Tibet was an integral part of China.

India’s Policy Towards Tibet

India’s policy towards Tibet has been shaped by its historical and cultural ties with the region. In 1950, India recognized Tibet as a part of China but also acknowledged the Dalai Lama as the spiritual leader of the Tibetan people. However, India’s policy has been criticized for being ambiguous and inconsistent.

Economic and Ecological Concerns

The Tibetan Plateau is home to several major rivers, including the Indus, Brahmaputra, and Yangtze, which are crucial for the region’s ecosystem. However, China’s increasing control over the region has raised concerns about the impact of its economic and infrastructure development on the environment.

The Importance of Tibets Independence

Tibet’s independence is crucial for the region’s ecosystem, culture, and identity. The Tibetan people have a unique culture and language, and their identity is closely tied to their Buddhist faith. The Chinese government’s control over Tibet has led to the suppression of Tibetan culture and language and the forced assimilation of Tibetans into Chinese culture.

Indias Options

India has several options to support Tibet’s independence, including:

- Recognize the Tibetan government-in-exile: India can recognize the Tibetan government-in-exile, led by the Dalai Lama, as the legitimate government of Tibet.

- Support the Tibetan freedom movement: India can support the Tibetan freedom movement by providing financial and diplomatic assistance to Tibetan activists and organizations.

- Raise awareness about Tibet: India can raise awareness about Tibet situation and the importance of its independence through various media channels and public events.

- Support Tibetan culture and language: India can support Tibetan culture and language by promoting Tibetan art, literature, and education in India.

Conclusion

The future of Tibet remains a crucial geopolitical challenge in India’s neighborhood. India’s policy towards Tibet has been inconsistent and ambiguous, and it is essential to re-evaluate its approach to supporting Tibet’s independence. By recognizing the Tibetan government-in-exile, supporting the Tibetan freedom movement, raising awareness about Tibet, and supporting Tibetan culture and language, India can play a crucial role in promoting Tibet’s independence and preserving its unique culture and identity.

US Policy on Tibet and its Significance

The Tibetan issue has been a longstanding concern in international politics, with the US playing a significant role in shaping the policy towards Tibet. In this summary, we will explore the history of the Tibetan issue, the significance of the US policy on Tibet, and the implications of this policy on the region.

A Brief History of the Tibetan Issue

Tibet has a complex history, with the country being ruled by various dynasties and empires, including the Mongol Empire and the Chinese Qing dynasty. In the early 20th century, Tibet declared its independence, but this was not recognized by China. In 1950, China annexed Tibet, leading to a long-standing conflict between the two countries.

The US Policy on Tibet

The US policy on Tibet has been shaped by several factors, including the country’s strategic interests in the region, human rights concerns, and the influence of the Tibetan diaspora community. In 1991, the US Congress passed the Tibetan Policy Act, which recognized Tibet as an occupied country and called for the protection of Tibetan human rights. In 2019, the US Congress passed the Tibetan Policy and Support Act, which reaffirmed the US commitment to Tibetan autonomy and human rights.

Significance of the US Policy on Tibet

The US policy on Tibet is significant for several reasons:

- Human Rights: The US policy on Tibet highlights the importance of human rights and democracy in the region. The Tibetan people have faced significant human rights abuses under Chinese rule, including restrictions on freedom of speech, assembly, and religion.

- Strategic Interests: Tibet is strategically located in the Himalayas, bordering India, Nepal, and Bhutan. The US policy on Tibet reflects the country’s strategic interests in the region, including the need to counter Chinese influence and promote stability.

- International Law: The US policy on Tibet is based on international law, including the principles of self-determination and territorial integrity. The US recognition of Tibet as an occupied country is based on the 1950 Tibetan Declaration of Independence.

Implications of the US Policy on Tibet

The US policy on Tibet has significant implications for the region:

- China-US Relations: The US policy on Tibet is a sensitive issue in China-US relations. China has consistently opposed US interference in its internal affairs, including Tibet.

- Tibetan Autonomy: The US policy on Tibet supports Tibetan autonomy and self-governance. This has implications for the Tibetan people, who have been seeking greater autonomy and human rights under Chinese rule.

- Regional Stability: The US policy on Tibet promotes regional stability and security. The Tibetan region is critical to the stability of the Himalayas, and the US policy on Tibet reflects the country’s commitment to promoting peace and security in the region.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the US policy on Tibet is a significant aspect of international relations, reflecting the country’s commitment to human rights, democracy, and strategic interests. The policy has implications for China-US relations, Tibetan autonomy, and regional stability. As the Tibetan issue continues to evolve, the US policy on Tibet will remain an important factor in shaping the region’s future.

The Future of Tibet and India’s Role

The Tibetan Plateau has been a point of contention for centuries, with various empires and nations vying for control. The current status of Tibet is a result of the complex history of the region, involving the Chinese Empire, British colonialism, and the Tibetan people’s struggle for independence.

A Brief History of Tibet

Tibet was an independent empire in the 7th century, with its own distinct culture and Buddhist tradition. The Tibetan Empire declined, and the region was later ruled by the Mongol Empire and the Chinese Yuan Dynasty. In the 13th century, Tibet was granted autonomy by the Chinese Emperor, with the understanding that the Tibetan government would manage its internal affairs while the Chinese Emperor would handle foreign affairs.

The British Expedition and the Lhasa Convention

In 1903, British forces, led by Sir Francis Younghusband, invaded Tibet, citing concerns about Russian influence in the region. The British government signed the Lhasa Convention with the Tibetan government, recognizing Tibet’s autonomy and establishing trade relations. However, the Chinese government disputed the convention, claiming sovereignty over Tibet.

The Fall of the Qing Dynasty and the Rise of the Communist Party

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 led to a power vacuum in Tibet. The 13th Dalai Lama, who had fled to India during the British expedition, returned to Tibet and declared independence. However, the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong, came to power in 1949 and claimed Tibet as part of China.

India Response and the Dalai Lamas Flight

In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled Tibet and sought refuge in India. The Indian government, led by Jawaharlal Nehru, provided asylum to the Dalai Lama but did not recognize Tibet as an independent nation. Instead, India adopted a policy of non-interference in Tibetan affairs and maintained diplomatic relations with China.

The Need for a New Strategy

India’s current policy towards Tibet is no longer tenable, given China’s increasing assertiveness and expansionist policies. India needs to reassess its relationship with Tibet and consider recognizing the Tibetan government-in-exile as a legitimate entity.

Steps Towards a New Strategy

- Improve the Public Profile of the Dalai Lama: India should promote the Dalai Lama’s image as a leader of the Tibetan people and not just a religious figure.

- Official Meetings and Recognition: Indian leaders should meet with the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan officials, recognizing their legitimacy and sovereignty.

- Recognition of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile: India should consider recognizing the Tibetan government-in-exile as a de facto government, providing it with diplomatic status and support.

- Counter-Strategy to China Plans: India should prepare for the possibility of China attempting to impose its own Dalai Lama and develop a counter-strategy to promote the Tibetan people’s right to self-determination.