Ashoka Conversion to Buddhism: A Reassessment

The popular narrative surrounding Emperor Ashoka the Great is largely a fabrication, built on a romanticized and historically inaccurate account of his life and conversion to Buddhism. Contrary to common belief, Ashoka wasn’t a Hindu king who found enlightenment after the brutal Kalinga war; he was likely a practicing Buddhist before it, and consistently a ruthless ruler motivated by political power.

The Myth vs. Reality:

Historians traditionally portray Ashoka as a remorseful conqueror who, horrified by the carnage of Kalinga, rejected Hinduism and embraced Buddhism, subsequently dedicating his reign to pacifism and dharma. This story is pervasive in Indian textbooks, particularly post-independence and shapes our understanding of him. However, there’s zero factual evidence to support a prior conversion to Hinduism. Becoming Buddhist isn’t a formal conversion it’s embracing the precepts and practices.

Timeline Early Violence Pre-Kalinga:

The truth is far more complex and darker. Ashoka ascended to the throne through violence, eliminating his half-brother the designated heir, and reportedly killing 99 of his siblings to consolidate power. This wasn’t an isolated incident. He then initiated a brutal persecution of both Jains and Ajivikas philosophical rivals likely due to their potential allegiance with family members he had slain. Think of it as a power consolidation mirroring Ottoman Sultans eliminating rivals upon enthronement. This persecution involved the deaths of thousands, undertaken while he was already a practicing Buddhist.

Kalinga: A Vassal State, Not a Noble War

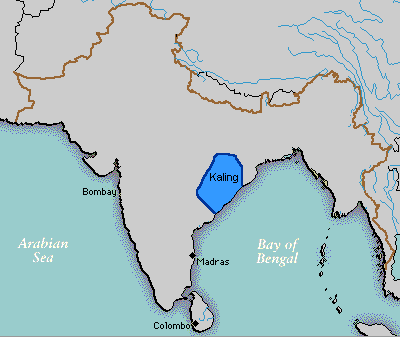

The Kalinga War itself may not have been the righteous conflict often depicted. Evidence suggests Kalinga was likely a vassal state or province of the Mauryan Empire, potentially rebelling against Ashoka’s rule. The battle resulted in the massacre of at least 100,000 Kalingan soldiers and the capture of 150,000 prisoners. Notably, Ashoka erected pillars advocating pacifism primarily in the west of India modern-day Afghanistan, not in Kalinga itself or the capital, Patliputra. This strongly suggests a political motive.

Political Posturing, Not Genuine Conversion:

Ashoka’s inscriptions promoting dhamma and pacifism were strategically placed essentially in public relations. He was a politician making a statement, not a saint experiencing a profound change of heart. The desire to portray him as a benevolent ruler appears to have been amplified post-Indian independence, alongside a deliberate effort to de-emphasize Hinduism and promote other faiths.

Chanda Ashoka The True Ashoka:

The historical Ashoka was known as Chanda Ashoka cruel Ashoka a dramatically different image than the peaceful monarch taught in textbooks. He was, in essence, a ruthless and ambitious ruler, who utilized Buddhist teachings for political gain while continuing to act with brutality and self-interest. The story we’ve been told is, to put it bluntly, a lie.

In essence, the narrative of Ashoka’s dramatic conversion is a significant oversimplification and distortion of a complex and often violent historical reality.

Ashok the Great: A Reassessment of History

The popular narrative of Ashoka, the Mauryan emperor, as a remorseful convert to Buddhism after the brutal Kalinga War, is largely a historical fabrication. The evidence overwhelmingly suggests Ashoka embraced Buddhist principles before the Kalinga conflict, and his reign was marked by violence and political maneuvering rather than solely pacifism.

Early Life Power Grab: Ashoka wasn’t the designated heir. His half-brother was the crown prince, away fighting at the western borders of the empire present-day Afghanistan. When Bindusara, their father, died, Ashoka seized the throne in a brutal coup involving the execution of approximately 99 of his siblings to eliminate rivals. This act earned him the moniker Chanda Ashoka, meaning fierce Ashoka.

Pre-Kalinga Buddhist Practice: Crucially, there’s no evidence of Ashoka converting after Kalinga. The evidence points towards Ashoka actively practicing Buddhist tenets prior to the war. Conversion in Buddhism isn’t a formal event; it’s a gradual adoption of philosophical precepts.

Religious Persecution Opposition: Ashoka’s rise wasn’t met with universal acceptance. The Jainas and Ajivika’s contemporary Dharmic philosophies potentially linked to opposing family members resisted his ascension. This led to a violent persecution of these groups, with thousands of Ajivikas reportedly killed. This isn’t framed as religious persecution in the modern sense but as a suppression of political opposition. He was, in fact, already a practicing Buddhist during this period of violence.

The Kalinga War A Subjugation, Not Conquest: The Kalinga War itself wasn’t a clash between independent entities. The historical context suggests Kalinga was likely a vassal state or province of the already vast Mauryan Empire. The war could have been triggered by a rebellion against Ashoka’s rule. The conflict was devastating: over 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were massacred, and 150,000 were taken prisoner.

Political Posturing Selective Pacifism: Ashoka’s famous pillars and inscriptions promoting pacifism weren’t evenly distributed. They were primarily erected in the western reaches of his empire modern-day Afghanistan and beyond rather than in regions like Kalinga or Patliputra the capital. This suggests these proclamations served a political purpose in image management rather than representing a genuine, across-the-board shift in policy. He was, to put it bluntly, projecting an image.

A Revisionist History: This reinterpretation stems from a questioning of traditional narratives that gained prominence after Indian independence. Some historians posit that a desire to downplay Hinduism and elevate other faiths influenced the creation of the saintly Ashoka myth, resulting in a fabricated story being presented in textbooks for generations. The truth, the video argues, is that Ashoka was a ruthless ruler who utilized Buddhist philosophies alongside brutal political tactics a far cry from the pacifist icon he’s often portrayed as.

Ashok: Beyond the Pacifist Myth – A Reassessment

The popular narrative of Ashoka the Great the remorseful Mauryan emperor who converted to Buddhism after the bloody conquest of Kalinga and embraced pacifism is largely a fabrication. Evidence suggests a far more complex and ruthless ruler, and challenges the timeline of his Buddhist leanings. There was no formal conversion to Buddhism; embracing Buddhist principles is a matter of practice, not ritual.

The Pre-Kalinga Buddhist: Contrary to popular belief, Ashoka likely adopted Buddhist tenets before the Kalinga war, not as a result of it. Historical evidence points towards this earlier adoption of Dharma.

A Throne Forged in Blood: Ashoka’s rise to power was far from peaceful. He seized the throne from his elder half-brother who was actively defending the empire’s western border, and then brutally consolidated his power. He is recorded as having killed approximately 99 of his siblings a scale comparable to Ottoman sultanic purges sparing only one brother. This paints a starkly different picture than the saintly image often presented.

Persecution of Jainas and Ajivikas: This consolidation wasn’t limited to family. The Jains and Ajivikas prominent philosophical schools at the time faced severe persecution. These groups likely opposed Ashoka’s claim to the throne possibly due to ties with executed family members, leading to a violent crackdown. Thousands of Ajivikas were killed, and Jains were also targeted. This wasn’t religious persecution per se, but a political purge eliminating opposition. At the time of these actions, Ashoka was already practicing Buddhist principles.

Kalinga: A Rebel Province, Not an Independent Kingdom: The Kalinga war itself needs recontextualization. Given the Mauryan Empire’s expansive reach, Kalinga was likely a vassal state or province, not an independent entity. The war may have been a response to rebellion against Ashoka’s rule. The battle resulted in a massacre of approximately 100,000 Kalingan soldiers killed and 150,000 taken prisoner.

The Inscriptions: Political PR, Not Sincere Conversion: Ashoka erected pillars and inscriptions proclaiming his devotion to pacifism and Dharma. However, these were primarily located in the western reaches of his empire present-day Afghanistan, not in the areas directly affected by the Kalinga war Kalinga or Pataliputra. This suggests a calculated political statement designed to project a specific image, akin to modern political rhetoric.

Chanda Ashoka A Cruel King: Ashoka was originally known as Chanda Ashoka Ashoka the Cruel a testament to his violent nature. The narrative of the pacifist king is a later construction, influenced by post-independence Indian political ideologies that sought to downplay Hinduism and promote other faiths.

In essence, the historical Ashoka was a complex figure a ruthless, ambitious ruler who already practiced Buddhism while enacting violent policies. The saintly image we have been taught is a carefully constructed myth

Ashok the Great: Debunking the Myth

The popular narrative of Ashoka the Great the remorseful emperor who converted to Buddhism after the brutal Kalinga war is largely a fabrication, a deliberately constructed historical revision. Contrary to popular belief, the evidence suggests Ashoka was a ruthless ruler before and during the Kalinga conflict, and was already embracing Buddhist principles.

A Violent Rise to Power: Ashoka wasn’t a benevolent heir. He seized the throne from his half-brother, who was engaged in defending the western borders of the Mauryan Empire modern-day Afghanistan. This wasn’t a peaceful transition; Ashoka killed approximately 99 of his siblings a calculated move to eliminate potential rivals, akin to the Ottoman practice of fratricide upon ascension. This period earned him the moniker Chanda Ashoka, meaning Ashoka the Fierce.

Pre-Kalinga Buddhist Practice: The claim Ashoka converted after Kalinga is unsupported. Numerous historical indicators point to his adoption of Buddhist precepts before the war. Becoming Buddhist isn’t a formal conversion its the integration of the dharma into daily life.

Persecution Political Consolidation: Ashoka’s rise wasn’t merely violent toward his family. He actively persecuted followers of Jainism and Ajivika philosophical schools of thought prevalent at the time. These groups potentially aligned with family members he eliminated, leading to a suppression of dissent. This wasn’t religious persecution in the modern sense, but a political maneuver to solidify his power. He reportedly had thousands of Ajivikas killed.

The Kalinga War: A Suppression of Rebellion The Kalinga War itself is often presented as an act of expansionist aggression. However, its likely Kalinga was already a vassal state or province of the Mauryan Empire. The conflict may have erupted due to Kalinga attempting to rebel against Ashoka’s new rule. The battle was devastating: at least 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were massacred, and another 150,000 were taken prisoner.

A Political Ploy: The Pillars Inscriptions: Ashoka commissioned pillars and inscriptions promoting dharma often interpreted as Buddhist teachings, but their placement is telling. These weren’t erected in regions that experienced his greatest brutality Kalinga or the capital, Pataliputra. Instead, they were concentrated in the western reaches of his empire modern-day Afghanistan. This suggests a calculated political strategy – projecting an image of peaceful governance to distant territories, rather than genuine remorse or commitment to non-violence. Think of it as ancient PR a king saying what people want to hear.

The Revisionist History: The current narrative surrounding Ashoka emerged after Indian independence. A political agenda aiming to downplay Hinduism and promote other faiths influenced the rewriting of history, creating the saintly Ashoka we know today. The truth, according to available evidence, is far more complex and, frankly, darker.

In essence, Ashoka wasn’t a king transformed by remorse; he was a ruthless, strategically-minded ruler leveraging Buddhist principles already embraced to strengthen his empire while carefully crafting a self-serving public image.

The Real Ashok: Debunking the Myth of a Peaceful Emperor

The popular narrative of Emperor Ashok Ashoka the Great Mauryan emperor is largely a fabrication. History paints him as a ruthless conqueror who, horrified by the carnage of the Kalinga war, converted to Buddhism and dedicated his life to pacifism. However, a closer examination of the evidence reveals a far more complex, and disturbing, truth: Ashok was a brutal ruler before, during, and after Kalinga, and his embrace of Buddhist principles doesn’t signify a dramatic moral conversion as commonly believed.

No Formal Conversion: The very idea of a formal conversion to Buddhism is misleading. Embracing Buddhist practices doesn’t require a ceremonial act. Historians claim Ashok adopted Buddhist tenets after Kalinga, but evidence suggests he likely began practicing before the war.

A Ruthless Rise to Power: Ashok didn’t inherit the throne peacefully. His father, Bindusara, had a designated crown prince Ashoks half-brother fighting in the northwest. When Bindusara died, Ashok seized the throne, killing his own brother and reportedly 99 of his other siblings to eliminate rivals a tactic akin to the brutal power grabs seen in Ottoman history where sultans routinely murdered family members upon ascension.

Persecution, Not Pacifism: Ashok’s consolidation of power wasn’t limited to fratricide. He violently suppressed opposing philosophical groups specifically the Ajivikas and Jains who may have been aligned with his slain siblings. This wasn’t religious tolerance; it was a calculated act of eliminating political opposition. Thousands of Ajivikas were killed, and Jains were persecuted. Importantly, this occurred while Ashok was already a practicing Buddhist.

The Kalinga War Its Context: The war with Kalinga is infamous for its bloodshed an estimated 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were massacred and 150,000 were taken prisoner. However, the narrative of Kalinga as a fully independent kingdom is likely incorrect. It was likely a vassal state or province of the expansive Mauryan empire. Rebellion or opposition to Ashok’s rule could explain the invasion. The name of the Kalingan king at the time remains unknown.

Political Propaganda, Not Genuine Change: Ashok erected pillars throughout his empire inscribed with edicts promoting pacifism and Buddhist principles. However, these pillars were conspicuously absent in Kalinga and Patliputra the Mauryan capital. They were concentrated in the western reaches of the empire, in present-day Afghanistan. This points to a strategic, political motive presentation to foreign territories rather than a genuine transformation of Ashok’s internal policies. He was essentially engaging in a calculated PR campaign.

Chanda Ashok – the Cruel Ashok: He was known historically as Chanda Ashok meaning wicked Ashok a testament to his brutality. The sanitized image of the benevolent emperor is a later construct. The modern retelling of Ashok’s story emerged after Indian independence, influenced by a desire to downplay Hinduism and promote other faiths.

In conclusion, the truth about Ashok Maurya drastically differs from the meticulously constructed myth. He wasn’t a reformed pacifist; he was a ruthless, calculating ruler who used religion as a tool for political control, masking a history of violence and bloodshed.

Ashoks Inscriptions: Beyond the Pacifist Myth

The widely accepted narrative of Emperor Ashok the great Mauryan ruler who embraced Buddhism after witnessing the horrors of the Kalinga war and subsequently became a champion of peace is largely a fabrication. Contrary to popular belief, evidence suggests Ashok wasn’t converting to Buddhism after Kalinga, but was likely a practicing Buddhist before the conflict. The story we have been told, heavily influenced by post-independence Indian political ideologies seeking to downplay Hinduism, paints a drastically inaccurate picture.

A Ruthless Rise to Power: Ashok didn’t inherit the throne peacefully. After the death of his father, Bindusara, while his half-brother fought off invaders in the northwest, Ashok seized power and violently consolidated it. He engaged in a brutal purge, killing approximately 99 of his siblings sparing only one in a manner akin to Ottoman sultanic tradition where brothers were routinely eliminated to secure the throne.

This wasnt a spiritual crisis driving his actions, but a power grab. This period saw a fierce suppression not of Hinduism generally, but of dissenting philosophical schools specifically the Ajivikas and Jains, who may have supported his rivals. Thousands were killed simply for opposing his ascension. This isn’t framed as religious persecution historically, but it was a ruthless political maneuver.

Kalinga: Not a Reaction, But Continuation: The infamous Kalinga war, frequently portrayed as the catalyst for Ashok transformation, was likely a suppression of rebellion within a province of the already expansive Mauryan Empire, not a war against an independent state. The scale of violence was horrific – at least 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were killed, and 150,000 were taken prisoner. Crucially, Ashok, at this time, was already a follower of Buddhist principles. This means the massacre wasn’t a result of a Hindu king’s brutality turning to Buddhism, but a Buddhist king enacting a brutal war.

The Political Inscriptions: The famous edicts and pillars attributed to Ashok weren’t a genuine outpouring of pacifism, but a calculated political strategy. The key observation These inscriptions promoting dharma and pacifism are overwhelmingly concentrated in the western reaches of his empire in present-day Afghanistan and beyond. There are no such inscriptions advocating peace in Kalinga itself, or even in the capital, Pataliputra

This is a telling detail. Ashok, known historically as Chanda Ashok Ashok the Fierce used Buddhist iconography and proclamations of peace to project a favorable image outside the regions where his brutality was most evident. He was a shrewd politician, doing what politicians do: crafting a narrative to suit his needs.

In essence, the narrative of Ashok’s conversion and pacifism is a myth. He was a ruthless leader, a practicing Buddhist during his aggressive campaigns and a master of political spin. The story we’ve inherited reflects a politically motivated reshaping of history, one that continues to be taught in textbooks today.

The Truth About Ashoka: Debunking the Myth of a Peaceful Convert

The popular narrative of Ashoka the Great Mauryan emperor who embraced Buddhism after a remorseful slaughter at Kalingais largely a fabrication, a rewriting of history driven by post-independence Indian political ideologies. The reality paints a far more complex, and far less flattering, picture.

Forget the Conversion Narrative: The idea of Ashoka converting from Hinduism to Buddhism is fundamentally flawed. Buddhism isn’t a religion you convert to in the traditional sense; its a practice embraced through aligning with its precepts. The evidence suggests Ashoka was already actively practicing Buddhist principles before the Kalinga war a crucial detail consistently overlooked.

A Ruthless Rise to Power: Let’s rewind a bit. Bindusara, Ashoka’s father, was the second Mauryan emperor. His designated heir was Ashoka’s half-brother, fighting invasions in the northwest. When Bindusara died, Ashoka seized the throne and brutally eliminated his rivals. The transcript draws a stark comparison to Ottoman sultanic tradition: almost like an Ottoman slaughter in which when an Ottoman sultan would be enthroned he would immediately on the same day kill all of his brothers and our brothers to ensure that there is no threat to his crown. He reportedly killed 99 of his siblings, sparing only one This wasn’t a peaceful ascension.

Persecution, Not Pacifism Even as a Buddhist: Following his power grab, Ashoka faced resistance from Jainas and Ajivikas, philosophical groups potentially aligned with his slain family members. Instead of tolerance, he unleashed a violent persecution against them a detail often omitted. Thousands of Ajivikas were killed, and Jains were also targeted. Crucially, this occurred while Ashoka was already practicing Buddhism. The transcript clarifies: that he did all of this while being a Buddhist. This challenges the simplistic narrative of a Hindu king becoming peaceful through Buddhism. The persecution wasn’t based on religious differences but on political opposition.

Kalinga: Rebellion, Not a Simple Conquest The infamous Kalinga war is often presented as a turning point, prompting Ashoka’s conversion. However, the transcript proposes a different interpretation: Kalinga was likely a vassal state or province of the Mauryan Empire. The war could have been a response to a rebellion or opposition to Ashoka’s rule. An estimated 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were killed, with 150,000 taken prisoner.

A Political Faade: Ashokas famed pillars and inscriptions promoting pacifism weren’t a genuine change of heart, but a calculated political maneuver. Notably, these inscriptions weren’t erected in Kalinga or Patliputra the capital, but in the far west of India, like present-day Afghanistan areas likely intended to impress and control conquered territories. He was, as the transcript bluntly states, just a political statement politicians say all kinds of things to appear nice, and that’s precisely what Ashok was doing. Before his pacifist image, he was known as Chanda Ashoka Evil Ashoka.

The Revisionist History: The modern narrative of a benevolent Ashoka is a relatively recent invention, emerging after Indian independence, driven by a desire to downplay Hinduism and promote other faiths. The transcript points out this rewriting of history happened to serve a political agenda: it is only after the Indian independence when uh well when a certain political ideology was adopted in India… so that’s when all these stories were concocted and placed in our textbooks.

In essence, Ashoka wasn’t a saintly convert; he was a ruthless ruler who leveraged Buddhist principles for political gain, perpetuating violence even while claiming to embrace peace. He wasn’t rejecting Hinduism, he was simply a Buddhist king consolidating power.

Ashok: Beyond the Pacifist Myth

The popular narrative of Emperor Ashok the remorseful conqueror who embraced Buddhism after the bloodshed of Kalinga is largely a fabrication. Contrary to common belief, there’s no evidence of a conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism, as the concept of conversion itself isn’t inherent to Buddhist practice embracing the dharma constitutes being Buddhist. The evidence strongly suggests Ashok actively practiced Buddhist principles before the Kalinga war, not as a result of it.

The story begins with a brutal power struggle. Upon the death of his father, Bindusar, Ashok seized the throne by eliminating nearly all 99 of his brothers a ruthlessly pragmatic move akin to Ottoman sultanic enthronements. This wasn’t a quest for religious purity, but raw political consolidation. This period saw persecution not of religion but of individuals tied to opposing family factions targeting Ajivikas and Jainas who resisted his ascent. Thousands of Ajivikas were killed, alongside persecution of Jains, not due to religious differences, but political opposition.

Ajivikas Lost Religion Of India

The Kalinga war itself, often depicted as the catalyst for Ashok pacifism, was likely a suppression of a rebellion within what was probably a vassal state or province of the expanding Mauryan Empire. At least 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were massacred and 150,000 were taken prisoner. Crucially, Ashok waged this war while already a practicing Buddhist.

He was known as Chanda Ashok wicked Ashok a far cry from the saintly figure often presented. His proclamations of pacifism weren’t universal. The edicts promoting ahimsa non-violence were prominently displayed in the western reaches of his empire present-day Afghanistan but never in Kalinga or his capital, Patliputra. These edicts were, fundamentally, political statements a facade crafted to project an image, much like modern-day political messaging.

This revised historical understanding emerged after Indian independence, influenced by a desire to diminish the prominence of Hinduism and elevate other faiths within the national narrative. The traditional story of a guilt-ridden Hindu king finding solace in Buddhism post-Kalinga is a myth, built upon a distortion of the historical record. Ashok wasn’t a convert to Buddhism, nor a pacifist he was a ruthless ruler who happened to be a practicing Buddhist while building and maintaining a vast empire through force.

The Distorted Legacy of Ashoka: Unpacking the NCRT Textbook Narrative

The popular portrayal of Ashoka the Great the Mauryan emperor who supposedly converted to Buddhism after a remorseful slaughter at Kalinga and became a champion of pacifism is largely a fabrication perpetuated by post-independence Indian textbooks. A closer look at the historical evidence reveals a far more complex, and unsettling, figure.

The Myth of Conversion: The idea of Ashoka converting from Hinduism to Buddhism is fundamentally flawed. Buddhism isn’t a religion requiring formal conversion; embracing Buddhist principles constitutes being Buddhist. Critically, evidence suggests Ashoka was already practicing Buddhist tenets before the Kalinga war, not as a result of it.

A Ruthless Rise to Power: Forget the image of a hesitant ruler. Ashoka seized the throne by eliminating rivals specifically, murdering his own half-brother the rightful heir returning from defending the western border, and reportedly 99 of his other siblings in a brutal power grab akin to Ottoman sultanic traditions of eliminating potential threats. This isn’t speculation; it’s recorded history, resembling a calculated purge to consolidate his rule.

Persecution, Not Pacifism: The narrative conveniently overlooks Ashoka’s earlier violent acts. He engaged in the persecution of Jainas and Ajivikas philosophical groups within the broader Dharmic tradition likely due to their opposition to his ascension. This wasn’t religious tolerance; it was a suppression of political resistance while he was already leaning toward Buddhist practices. Thousands of Ajivikas were reportedly killed.

Kalinga: A Province, Not an Independent Kingdom: The story paints Kalinga as a victim of Ashoka’s sudden change of heart. However, the Mauryan Empire was expansionist and vast, stretching far beyond modern India. It is improbable Kalinga, located adjacent to the capital Pataliputra, would have been allowed to exist as an independent state. It was likely a vassal state or province, and the conflict may have stemmed from rebellion or resistance after Ashoka took power. The battle resulted in a devastating loss of life over 100,000 Kalingan soldiers were killed and 150,000 were taken prisoner.

A Political PR Campaign: The inscriptions extolling pacifism weren’t universal. They were strategically placed in the western reaches of his empire modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan a clear indication of political messaging aimed outward, not genuine internal reform. Notably, no such proclamations were erected in Kalinga or Pataliputra. This suggests Ashoka’s pacifism was largely a public relations exercise.

Chanda Ashoka: The Real Ashoka Historically, Ashoka was known as Chanda Ashoka’s cruel Ashoka a stark contrast to the saintly image projected in textbooks. He was a ruthless, expansionist ruler who utilized propaganda to craft a favorable narrative.

Why the Distortion This revisionist history gained traction in post-independence India, driven by a political agenda to downplay Hinduism and promote a more favorable view of other faiths. The narrative was constructed discovered and presented as historical truth.

In essence, the Ashoka we’ve been taught about is a carefully curated myth, obscuring the reality of a complex and often brutal ruler. The truth, as presented by historical evidence, depicts a pragmatic politician who skillfully employed religious symbolism to legitimize his power and control a vast empire