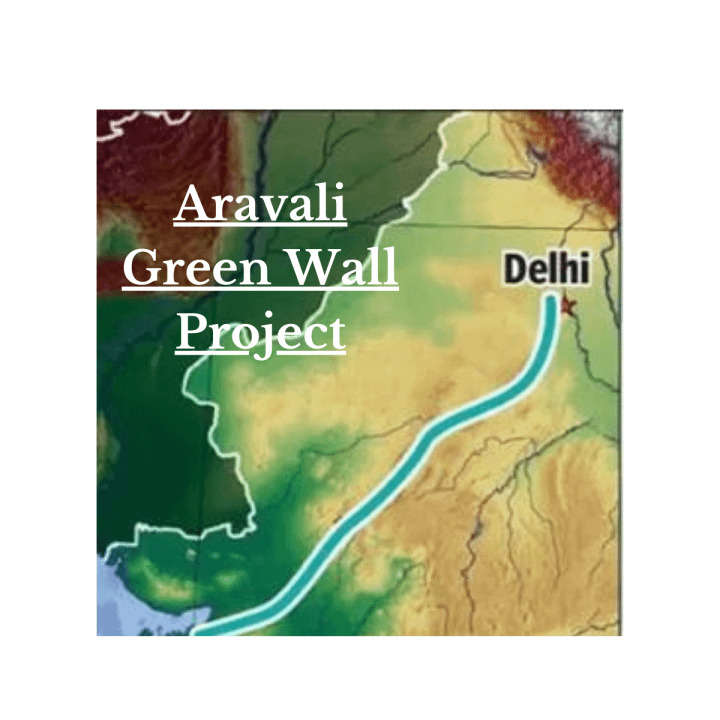

India is building the “Great Green Wall,” also known as the Aravalli Green Wall Project, across the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi to combat pressing environmental challenges such as desertification, land degradation, and climate change. This ambitious initiative involves creating a 1,400-kilometer-long and 5-kilometer-wide green belt of trees and vegetation, stretching from Porbandar in Gujarat to Panipat near the Delhi-Haryana border, along the Aravalli Hill Range. Below is a detailed explanation of why India is undertaking this project.

1. Combatting Desertification and the Thar Desert’s Eastward Expansion

The primary motivation for the Great Green Wall is to halt the eastward spread of the Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert, located in western Rajasthan and extending into parts of Gujarat and Pakistan. The desert’s expansion is driven by factors like deforestation, overgrazing, unsustainable agricultural practices, and climate change, which have degraded the natural barrier provided by the Aravalli Range. This ancient mountain range, stretching over 800 kilometers, historically acted as a shield, separating the arid Thar region from the fertile plains of North India. However, decades of illegal mining, deforestation, and urbanization have stripped the Aravallis of much of their green cover, weakening this barrier.

By planting native trees and shrubs along the Aravalli corridor, the project aims to restore this ecological shield, preventing desert sands, dust storms, and arid conditions from encroaching into the fertile Gangetic plains, including Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh—often referred to as India’s “granary.” This is critical not only for environmental stability but also for protecting agricultural productivity and food security in North India.

2. Addressing Land Degradation

India faces a severe land degradation crisis, with approximately 96.4 million hectares (29.3% of its total geographical area) classified as degraded, according to the Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas of India (ISRO, 2016). The states targeted by the Green Wall—Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi—are among the worst affected, with over 50% of their land degraded or at risk of desertification. The Aravalli region itself has seen significant deterioration, with 2.3 million hectares of its land currently degraded due to mining, soil erosion, and loss of vegetation.

The Green Wall seeks to rehabilitate this degraded land through large-scale afforestation, soil conservation, and water management initiatives. By restoring 1.15 million hectares of degraded land by 2027, the project aligns with India’s national commitment under the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) to restore 26 million hectares by 2030.

3. Mitigating Climate Change and Air Pollution

The Great Green Wall serves as a climate resilience strategy by acting as a carbon sink. The planting of an estimated 135 crore (1.35 billion) native trees over the next decade is projected to sequester around 250 million tons of carbon by 2030, contributing to India’s pledges under the Paris Agreement and UNFCCC. This carbon sequestration will help offset greenhouse gas emissions, a pressing need given India’s industrial growth and urban expansion.

Additionally, the green belt will act as a physical barrier against dust storms originating from the Thar Desert and western Pakistan, which significantly contribute to air pollution in the Delhi-NCR region. Delhi’s air quality, often among the world’s worst, is exacerbated by dust (accounting for a notable portion of its PM10 levels) alongside industrial emissions, vehicular pollution, and crop burning. The Green Wall aims to reduce this dust influx, improving air quality and public health in North India.

4. Enhancing Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

The Aravalli Range is home to unique biodiversity, including endemic plants, animals, and microorganisms, many of which are under threat due to habitat loss. The Green Wall project prioritizes planting native species like neem, peepal, and banyan, which are well-adapted to local conditions and support the region’s ecosystems. This will help revive habitats for wildlife, enhance soil quality, and recharge groundwater—services that have been disrupted by decades of environmental neglect.

The project also includes rejuvenating 75 water bodies in its initial phase (five per district across the Aravalli landscape), starting with areas like Gurgaon, Faridabad, and Rewari in Haryana. Improved water retention and soil stabilization will mitigate droughts and floods, bolstering ecological resilience.

5. Socio-Economic Benefits and Community Empowerment

Beyond environmental goals, the Green Wall is designed to uplift local communities. It aims to create millions of “green jobs” through tree planting, maintenance, and agroforestry initiatives, mirroring the African Great Green Wall’s target of 10 million jobs by 2030. In states like Haryana, where 35,000 hectares are slated for restoration, rural populations will benefit from employment opportunities and resources like timber, fodder, and non-timber forest products.

Agroforestry will also integrate sustainable farming practices, providing farmers with additional income sources while reducing pressure on degraded lands. This socio-economic dimension ensures community ownership, increasing the project’s long-term viability.

6. Inspiration from Africa’s Great Green Wall

The Indian initiative draws inspiration from Africa’s Great Green Wall, launched in 2007 by the African Union to combat desertification across the Sahel region, from Senegal to Djibouti. Spanning 8,000 kilometers, the African project has restored millions of hectares, improved food security, and showcased the power of collective action against environmental degradation. India’s Green Wall adapts this model to its context, focusing on the Aravalli corridor as a critical frontline against desertification, with a phased approach and multi-stakeholder collaboration involving governments, forest departments, research institutes, and local communities.

7. Strategic and Geopolitical Significance

The Aravallis influence Northwest India’s climate by guiding monsoon clouds eastward and shielding the plains from cold Central Asian winds. Preserving this range through the Green Wall ensures climatic stability for a region that feeds millions. Additionally, by positioning itself as a leader in green development, India enhances its global image under international frameworks like the UNCCD, CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity), and UNFCCC, reinforcing its commitment to sustainable development goals.

Conclusion

India is building the Great Green Wall across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi to tackle the interconnected crises of desertification, land degradation, climate change, and biodiversity loss while fostering economic growth and resilience. Launched in 2023 by the Union Environment Ministry and accelerated in 2025, this project is a strategic response to the eastward march of the Thar Desert and the degradation of the Aravalli Range. By restoring ecosystems, sequestering carbon, improving air quality, and empowering communities, the Green Wall aims to secure a sustainable future for North India, potentially setting a precedent for green initiatives worldwide. As of March 20, 2025, with plans to restore vast tracts by 2027 and complete the vision by 2030–2041, it stands as a testament to India’s resolve to balance development with environmental stewardship.