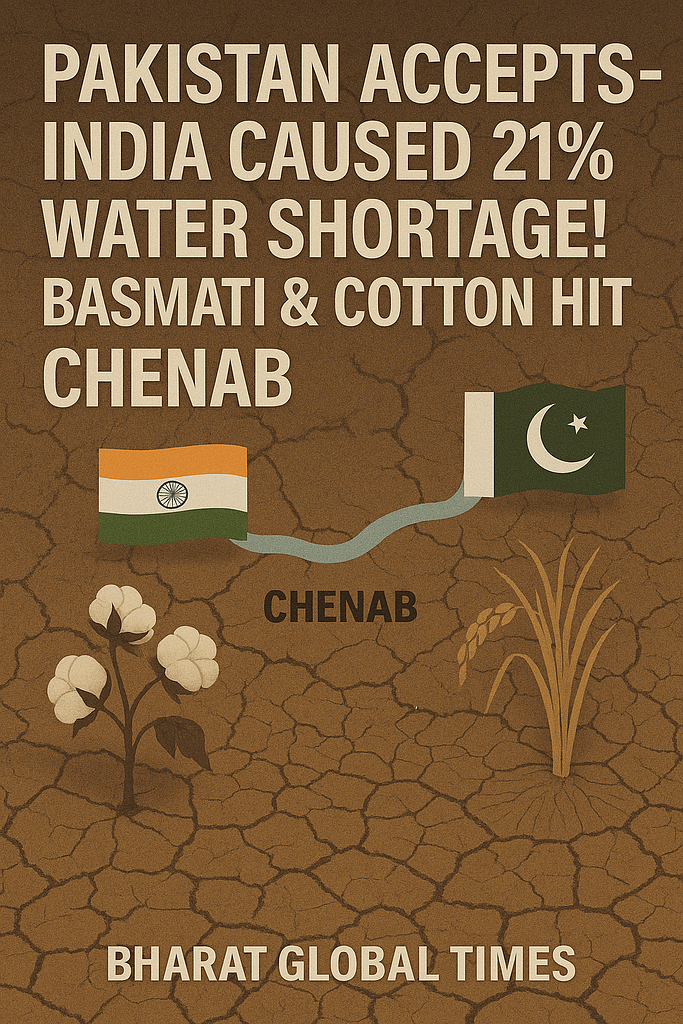

Islamabad/New Delhi, May 6, 2025 — In a rare and significant admission, Pakistani officials have acknowledged that India’s upstream water control has contributed to a 21% water shortage in several agricultural regions of Pakistan — hitting key crops like basmati rice and cotton especially hard.

This comes amid rising tensions over the Chenab River, with some Pakistani commentators and political leaders even calling India’s actions an “Act of War” under the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty.

Agricultural Sector Takes the Hit

Pakistani farmers in Punjab and Sindh are already reeling. Basmati fields are drying out earlier than usual, and cotton sowing has been delayed across several districts. According to officials from Pakistan’s Ministry of Water Resources, the reduced flow in the Chenab has drastically lowered irrigation availability during a critical phase of planting.

“This isn’t just about water. This is about livelihoods, food security, and an entire rural economy coming under stress,” said a senior Pakistani agriculture officer in Lahore.

The Chenab Dispute: Old Tensions, New Accusations

The Chenab River, which flows from India into Pakistan, is governed under the Indus Waters Treaty — a decades-old agreement brokered by the World Bank. While India is allowed to build limited infrastructure like run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects, Pakistan claims recent Indian actions have exceeded treaty limits, leading to major flow disruptions.

Indian officials have rejected the “act of war” narrative, calling the accusations “politically motivated” and maintaining that all dam and canal projects on Indian soil remain fully compliant with treaty obligations.

India’s Position: Within Treaty Boundaries

Sources in India’s Ministry of Jal Shakti (Water Resources) say India is simply exercising its rights under the treaty to utilize water for hydropower and irrigation in Jammu & Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. They argue that Pakistan has failed to modernize its own water storage and infrastructure, which worsens its seasonal shortages.

“We are using our fair share. Any claims beyond that are misplaced and aimed at stoking unnecessary alarm,” an Indian official told Bharat Global Time on condition of anonymity.

Basmati & Cotton Exports at Risk

With water scarcity hitting yields, Pakistan’s export sector could face serious setbacks. Basmati rice — a prized export — and cotton, which fuels Pakistan’s textile industry, are both water-intensive. Initial estimates suggest a 10–15% drop in production if the situation isn’t resolved within the next few weeks.

Local farmers fear the worst. “If this continues, we won’t just lose crops. We’ll lose our place in global markets,” said Asif Mahmood, a cotton grower near Multan.

A Call for Talks — But Will They Happen?

Diplomatic sources say backchannel talks are underway, though no formal bilateral meeting has been scheduled. Analysts warn that escalating water tensions between the two nuclear-armed neighbors could have wider geopolitical consequences, especially with climate change already reducing snowmelt and river flows in the Himalayas.

The Bigger Picture: Water as a Future Flashpoint

As rivers dry up and populations grow, water is increasingly being seen not just as a resource — but a weapon. Both India and Pakistan are now under pressure to revisit how the Indus Waters Treaty functions in today’s climate-stressed reality.