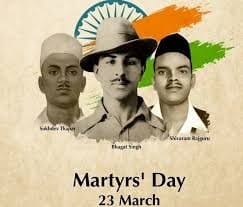

On March 23, 1931, the British colonial government executed three young revolutionaries—Bhagat Singh, Shivaram Rajguru, and Sukhdev Thapar—for their role in the Lahore Conspiracy Case and the assassination of British police officer John Saunders. Their deaths sent shockwaves through India, galvanizing the freedom struggle with their martyrdom. Yet, one question lingers in the minds of many even today: Why didn’t Mahatma Gandhi, the towering figure of India’s independence movement, step in to save them?

It’s a question steeped in historical complexity, ideological differences, and political pragmatism. Let’s unpack the reasons behind Gandhi’s stance and the events that shaped this pivotal moment in India’s fight for freedom.

Gandhi and the Revolutionaries: A Clash of Ideologies

At the heart of this story lies a fundamental divide between two visions for India’s liberation. Gandhi was the apostle of Ahimsa (non-violence), advocating peaceful resistance against British rule through mass movements like the Dandi Salt March and civil disobedience. His philosophy rested on the belief that moral superiority and unity could dismantle colonial oppression without bloodshed.

Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev, however, belonged to a different school of thought. Inspired by socialism and revolutionary zeal, they saw armed struggle as a necessary response to British tyranny. Their actions—like the bombing of the Central Legislative Assembly in 1929 and Saunders’ assassination—were meant to awaken a nation they felt had grown complacent under oppression. For them, violence was a tool of justice, not a betrayal of the cause.

This ideological rift made it difficult for Gandhi to fully embrace the trio’s methods, even as he admired their courage and patriotism. In his writings, Gandhi acknowledged Bhagat Singh’s bravery but argued that violent acts, however noble in intent, risked alienating the masses and giving the British an excuse to intensify their repression.

The Gandhi-Irwin Pact: A Strategic Compromise

In early 1931, Gandhi was negotiating the Gandhi-Irwin Pact with Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India. Signed on March 5, this agreement was a fragile truce: Gandhi agreed to suspend the Civil Disobedience Movement, and in return, the British promised to release political prisoners (excluding those convicted of violent crimes) and lift certain repressive measures. For Gandhi, this was a tactical move to consolidate the Congress’s position and maintain momentum in the broader struggle.

Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev, however, were not covered under this amnesty. Their death sentences had been confirmed by the courts, and the British saw them as dangerous symbols of rebellion. Gandhi did raise their case with Irwin, urging clemency during their talks. Historical accounts suggest he wrote letters and made verbal appeals, arguing that sparing their lives would foster goodwill. Yet, Irwin remained unmoved, viewing the executions as a necessary show of imperial strength.

Critics argue Gandhi could have pushed harder—perhaps by threatening to break the pact. But Gandhi likely saw this as a gamble that could unravel the fragile gains of the agreement and fracture the unity of the independence movement. His focus was on the long game, not a single battle.

Public Pressure and Political Realities

By 1931, Bhagat Singh had become a national hero, especially among the youth. His charisma, intellect, and defiance—captured in slogans like “Inquilab Zindabad” (Long Live the Revolution)—ignited a fervor that rivaled Gandhi’s popularity. Protests erupted across India as the execution date loomed, with many pleading for Gandhi to intervene.

Gandhi faced a dilemma. Supporting the revolutionaries risked endorsing violence, which could undermine his non-violent creed and alienate moderate supporters within the Congress. Conversely, doing nothing might tarnish his image as a leader who stood for all Indians. In a speech at the Karachi Congress session shortly after the executions, Gandhi expressed sorrow over their deaths but reiterated his belief that their path was misguided. He mourned their loss as patriots but stood firm on his principles.

Did Gandhi Have the Power to Save Them?

Some historians argue that Gandhi’s influence over the British was overstated. While he commanded immense moral authority among Indians, the colonial administration often saw him as a negotiator, not a dictator of terms. The British were determined to execute Bhagat Singh and his comrades to crush the revolutionary movement and deter others. Even if Gandhi had escalated his efforts—say, by launching a hunger strike—it’s uncertain whether the Raj would have relented.

Moreover, Gandhi’s leverage was limited by the legal process. The trio’s fate rested with the Privy Council in London, and their appeal had been rejected. By the time Gandhi entered negotiations with Irwin, the window for clemency was narrowing. The executions were carried out hastily on March 23—earlier than the scheduled date—perhaps to preempt further agitation.

A Legacy of Sacrifice and Reflection

The executions of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev left an indelible mark on India’s freedom struggle. Their deaths fueled outrage that strengthened the movement, proving that even in defeat, they achieved their goal of awakening the nation. Gandhi continued his non-violent crusade, leading India to independence in 1947—a victory that owed much to the diverse strands of resistance, including the revolutionaries he couldn’t save.

So, why didn’t Gandhi save them? It wasn’t a lack of compassion or courage but a collision of principles, priorities, and political constraints. Gandhi chose a path he believed would liberate millions, even if it meant sacrificing three. Whether that choice was right or wrong remains a matter of debate—a poignant reminder that history is rarely black and white.

What do you think? Could Gandhi have done more, or was his hands tied by the times? Let’s discuss below.